by Rishidev Chaudhuri

Like some nervous Gnostic, I’m oppressed by matter, and I’m never as aware of it when I move. Then, more than ever, I seem to exist in a whirl of paper and clothes and small objects of no apparent purpose that all conspire to cloud my existence and subvert the clear paths of my reason. Every time I put something down I lose it. Every time I look away, matter accumulates in the interstices of my life, spills from behind me, wells up through the crevasses of my mind and wraps around my feet. Objects make me anxious. I need to consider each one carefully before I throw it away, in case I need it, and then I am relieved when it is gone. I devise organizational schemes and administrative techniques but matter is stubborn and slippery and in the absence of a neurosis-inducing constant vigilance it squirms away and will not be subdued. I think of this as I wade through all the matter that has accumulated in my life: all the stuff that I need to sort through, each object I need to sorrowfully consider and reject.

Like some nervous Gnostic, I’m oppressed by matter, and I’m never as aware of it when I move. Then, more than ever, I seem to exist in a whirl of paper and clothes and small objects of no apparent purpose that all conspire to cloud my existence and subvert the clear paths of my reason. Every time I put something down I lose it. Every time I look away, matter accumulates in the interstices of my life, spills from behind me, wells up through the crevasses of my mind and wraps around my feet. Objects make me anxious. I need to consider each one carefully before I throw it away, in case I need it, and then I am relieved when it is gone. I devise organizational schemes and administrative techniques but matter is stubborn and slippery and in the absence of a neurosis-inducing constant vigilance it squirms away and will not be subdued. I think of this as I wade through all the matter that has accumulated in my life: all the stuff that I need to sort through, each object I need to sorrowfully consider and reject.

Thankfully, History is helping. I liked tapes and CDs, but I don’t miss them and I’m relieved that they’ve vanished into pure Spirit (or whatever their ultimate end is). It was always hard to tell what music I owned and hard to find it and hard to decide what to take where, and I constantly found CDs in strange places and they have hard edges. I hated writing by hand. It was slow and painful and brought back unpleasant memories of frantically scratching away in a school book. I love the rapid erasure and recreating of digital writing; I love the ease of structuring information liberated from a particular physical correlate. And I especially like that I don’t have to carry stacks of notes with me.

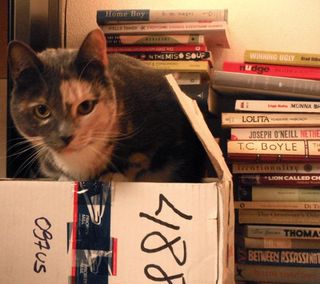

And yet, despite this progressive horror of the material, I seek out and accumulate books wherever I go, and I crave their presence. They follow me around, like expensive wallpaper that I need to feel settled in a place. They’re the first thing I think of when I think of my room or what I need to move, and not having my books around me marks transience. At this point, most of what I need to pack seems to be books. I buy more books than I need or will read. I travel with books I’ve already read and probably won’t read again. Deciding which books to take where is a weighty matter, like constructing an intellectual and emotional landscape that will determine my journey.

In theory, I find the idea of e-books somewhat compelling. They seem brisk and efficient and the idea that a single small object can contain hundreds of books is especially enticing as I contemplate moving a room full of bookshelves. And yet I never use them. I read fifty pages on an e-book reader once and it was pleasant, but I’ve never done it since. It doesn’t strike me as an imaginative possibility; it just doesn’t seem part of the possible configurations that my experience allows.

It’s not that I like the smell of books, or their weight, or the memories lying in bed and reading brings back, though I do like all of these things. It’s not just that I like walking into someone’s home and seeing their mind laid out on their bookshelves or that I like the physical act of lending a book and returning a book. It seems somehow baser, something not just pre-cognitive but pre-emotional, like that their material presence has so shaped my way of interacting with the world that their absence troubles the unity of my experience. I imagine this is what it is to have your world determined by a certain technology in its particularity and to suddenly realize that that technology is slipping away. This seems like a common sentiment among the people I know (though it’s often expressed as, and I think confused with, an aesthetic disagreement with e-books). Perhaps we’re already part of an older generation that starts to find the world it’s growing into dissonant. I recognize that at some point in my life I’ll have to move to reading books electronically. I don’t know how this moment will come or what sort of person I’ll be then. I’m not even sure what I’ll have left to put in my room.