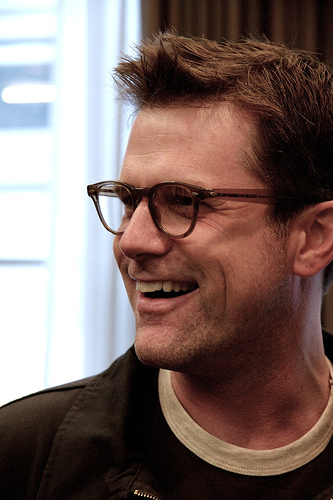

Merlin Mann is a writer, speaker, blogger, podcaster and student of the creative mind. He's the creator of 43Folders, a popular web site devoted to time, attention and creative work, as well as the man behind such varied projects as The Merlin Show, Kung Fu Grippe, 5ives, the 43Folders podcast, one-third of the crazy-successful comedy podcast You Look Nice Today, and lord knows what else. He's also currently working on his first book, Inbox Zero. Colin Marshall originally conducted this conversation on the public radio program and podcast The Marketplace of Ideas. [MP3] [iTunes link]

There has rarely been a man to whom the title “productivity guru” has been applied so often who has less wanted to be called a productivity guru. What's your relationship to that label these days?

There has rarely been a man to whom the title “productivity guru” has been applied so often who has less wanted to be called a productivity guru. What's your relationship to that label these days?

Oh, man. The thing is, if you're like me and you hear the word “guru,” you expect it to be in a headline with either “swindle” or “ponzi.” It's a tremendous compliment when people say that. I think people say that because the 43Folders web site became fairly well known for trying to help people with the same kinds of problems that I have historically suffered from. It becomes a little bit of an albatross at a point, because — I'm not sandbagging — I honestly don't consider myself anywhere near the level of expertise that would qualify me as a guru. I think the reason people like what I do — I hope — is because I'm not saying, “Here's how to be great like me.” It's like, “Here's how to hopefully suck less, like me, some days.” For the kind of stuff I'm talking about, that's pretty different than a lot of the “gurus.” I just don't want to give people the wrong idea.

How much was that the need that 43Folders tapped into when it first became really successful? How much was that honesty part of it — or what need were you tapping into with the site?

There's a couple parts. One is definitely is the timing. It's funny; there's these certain things that come along where, after it's been around a while, you start to think, “Oh gosh, that's probably been around forever.” You hear Nirvana and you go, “Oh my gosh, how have we not had Nirvana forever? It seems so obvious now.” At the time, it seemed pretty crazy to have a web site about Mac software and life hacks and personal productivity and these goofy programs like Quicksilver that I like a lot. At the time I thought, “This has got to be the most insane idea in the world.”

Different people liked the site for very different reasons. I think I really hit a zeitgeist; I was standing in the right line at the right time. The topics of attention management and wanting to deal with this feeling of being overwhelmed by information and calls on our attention became a hot topic around the time I started doing it. I think I helped contribute to the popularity of those ideas, but I think it was good timing. The voice was part of it. I think that's true for blogs; I think that's true for podcasts; it's definitely true in radio. A lot of people don't care about a topic as much as they care about the voice of the person talking about it, for better or for worse. I hope that's why people enjoy it.

When I first became a reader of your site and when a lot of my friends did, we came to it because these topics have a very broad appeal. Who doesn't want to be more productive? But I found myself virtually among your fans, and what I saw around me was a lot of guys with chunky glasses. They love Apple products and they like to write in their Italian notebooks and they care a lot about the kerning of the font Helvetica. Could you enrich this mental image I have? Who are these people?

That's interesting. So you're doing some audience segmentation? You'd say that's part of my demo?

Read more »

At a lunch party I was placed next to a well-known female rabbi, now ennobled. She asked me, somewhat belligerently, whether I said grace when it was my turn to do so at High Table dinner in my Oxford college. “Yes,” I replied, “Out of simple good manners and respect for the medieval traditions of my college.” She attacked me for hypocrisy, and was not amused when I quoted the great philosopher A J (Freddy) Ayer, who also was quite happy to recite the grace at the same college when he chanced to be Senior Fellow: “I will not utter falsehoods”, said Freddy genially, “But I have no objection to making meaningless statements.”