by Stefany Anne Golberg

by Stefany Anne Golberg

Wes Anderson is a dandy who would make Oscar Wilde proud. Of all the sizzling epigrams that geysered out of Wilde’s pen, a favorite is, “A really well-made buttonhole is the only link between Art and Nature”. It’s a very dandy thing to say. Dandies like Wilde don't think that nature has any authority over art. They think the opposite. In dandyland, nature and reality imitate art. In other words, when we look at nature we see every nature painting and every National Geographic documentary we've ever seen. There is no “real reality” for humans without the human touch; nature is pretending to be art.

Wes Anderson’s dandy films bend reality over and paint a fuchsia moustache on its bum. They are sculpted and posed. They aren’t necessarily fake, like fantasy fake, but they are full of fakers. In all of them, the main character is a regular person upon appearance, but is basically an amateur and a fraud, playacting at greatness. Rushmore is the story of a teenage boy who masquerades as the king of his boarding school, but, in fact, he is a horrible student. The Life Aquatic is the story of a famous oceanographer, who is more interested in daring feats than science. Royal Tenenbaum, in The Royal Tenenbaums, is a wealthy and excellent lawyer, except that he has been disbarred and is a son-of-a bitch. These films are advertisements for the aestheticized life. Like Wilde, there is no true nature for Wes Anderson. Our authentic state is the one we imagine for ourselves, the trumped-up life we've convinced other people is impressive.

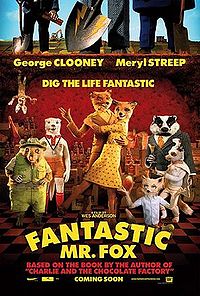

More than any of his previous films, The Fantastic Mr. Fox is a really well-made buttonhole. 'I didn't want it so much to be more realistic,' Anderson told the Telegraph, 'I wanted it to be more ours.' Anderson elaborates on Roald Dahl’s book with dandy aplomb. In both tales, we have a family of foxes—Mrs. Fox, little children foxes, and the eponymous Fantastic Mr.—intent on getting their daily bread by stealing it from the valley’s three farmers: Farmer Boggis, Farmer Bunce, and Farmer Bean. An epic battle ensues between animals and farmers, each trying to outsmart the other. Mr. Fox thieves not because it is necessary, but because it’s more fun than foraging in the wild like other animals. “I'm just a wild animal,” Fox says with a sigh. But his regret is not very convincing. This is a fox who sports a double-breasted corduroy suit after all. Getting his food from farmers instead of hunting is the wildness of Mr. Fox. In other words, his “natural” state is to act against nature.

Read more »

In fact, many hypothermia victims die each year in the process of being rescued. In “rewarming shock,” the constricted capillaries reopen almost all at once, causing a sudden drop in blood pressure. The slightest movement can send a victim's heart muscle into wild spasms of ventricular fibrillation. In 1980, 16 shipwrecked Danish fishermen were hauled to safety after an hour and a half in the frigid North Sea. They then walked across the deck of the rescue ship, stepped below for a hot drink, and dropped dead, all 16 of them.