by Mike Bendzela

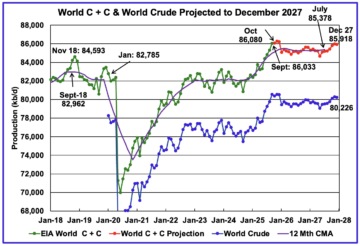

Around the year 2005 I stumbled upon a rather disturbing website called DieOff.org, which is no longer extant. (Don’t try to go there: The url now leads to porn.) Run by the late Jay Hanson, it provided a wide-lens view of humanity’s future based on such physical realities as ecology, mining and minerals depletion and, most importantly, declining energy resources, in particular the fossil fuels. It seemed our species’ prospects were rather stark and dim (hence the site’s name). There I discovered an important article by geologists Colin J. Campbell and Jean H. Laherrere called “The End of Cheap Oil,” first published in Scientific American in 1998.

I immediately recognized that I was re-encountering some of the lessons I learned in an influential college course I took in 1980 called Geology and Human Affairs, taught by professor Mark J. Camp at the University of Toledo in Ohio, co-author of Ohio Oil and Gas. I had just dropped my geology major, simply because I couldn’t hack the math and chemistry, but even as a humanities major I wanted to keep taking science courses. Camp’s course was listed as being for non-majors, so I enrolled, thinking I would be learning about historic earthquakes and volcanic eruptions, and perhaps about the uses of precious gems and minerals and such. Happily, I turned out to be very mistaken. It was a course I would never forget.

Camp’s course was a tour (and tour de force) through modern humanity’s dependence on the fossil fuels and other planetary energy resources. Read more »

My friend Arjuna is an archer in the army. He has been on several campaigns, always victorious. His bow is as tall as he is. It is made of wood but strengthened with sinews. The combination makes it firm, supple and elastic. I say that, and marvel at the expert ease with which he handles it, and I know I – man of letters and numbers as I am – would never be able to pull the string back as he does.

My friend Arjuna is an archer in the army. He has been on several campaigns, always victorious. His bow is as tall as he is. It is made of wood but strengthened with sinews. The combination makes it firm, supple and elastic. I say that, and marvel at the expert ease with which he handles it, and I know I – man of letters and numbers as I am – would never be able to pull the string back as he does.

SUGHRA RAZA. Shadows On The Riverbed. Celestun, Mexico, March 2025.

SUGHRA RAZA. Shadows On The Riverbed. Celestun, Mexico, March 2025. In 2007, the neuroscientist Sabrina Tom slid volunteers into an fMRI scanner at UCLA and offered them coin-flip gambles. Win twenty dollars or lose twenty. Win thirty or lose ten. Will you take the bet? Most people refused any gamble where the potential loss exceeded about half the potential gain. The scans showed why: as potential losses grew, the brain’s reward regions responded more sharply to what could be lost than to what could be gained. Loss aversion — losing something hurts roughly twice as much as gaining it feels good — was visible in the tissue.

In 2007, the neuroscientist Sabrina Tom slid volunteers into an fMRI scanner at UCLA and offered them coin-flip gambles. Win twenty dollars or lose twenty. Win thirty or lose ten. Will you take the bet? Most people refused any gamble where the potential loss exceeded about half the potential gain. The scans showed why: as potential losses grew, the brain’s reward regions responded more sharply to what could be lost than to what could be gained. Loss aversion — losing something hurts roughly twice as much as gaining it feels good — was visible in the tissue. Allopathy and homeopathy are two contrasting theories of medicine. Allo, meaning other, and homo, meaning same, indicate how suffering (pathos) is cured in these two approaches. Modern medicine, speaking generally, is based on the principle of allopathy, meaning that sickness is counteracted by healing and therapeutic treatments; homeopathy, often considered alternative medicine or pseudoscience, is based on the idea that “like cures like,” so rather than introducing an antidote to an illness, the medicine used is meant to produce a response similar to the illness itself, stimulating the body’s natural healing mechanisms and curing the underlying ailment.

Allopathy and homeopathy are two contrasting theories of medicine. Allo, meaning other, and homo, meaning same, indicate how suffering (pathos) is cured in these two approaches. Modern medicine, speaking generally, is based on the principle of allopathy, meaning that sickness is counteracted by healing and therapeutic treatments; homeopathy, often considered alternative medicine or pseudoscience, is based on the idea that “like cures like,” so rather than introducing an antidote to an illness, the medicine used is meant to produce a response similar to the illness itself, stimulating the body’s natural healing mechanisms and curing the underlying ailment.

Political discussions and debates leave me cold. That’s because I abhor conflict, and politics always seem to be accompanied by disagreements, fights, raised voices, and anger. When I think about the hot topics in the 60s and 70s, many of them centered on matters of race, I associate those times with images of red-faced individuals confronting one another, not infrequently accompanied by fists, even guns. Sometimes soldiers or militias or mobs.

Political discussions and debates leave me cold. That’s because I abhor conflict, and politics always seem to be accompanied by disagreements, fights, raised voices, and anger. When I think about the hot topics in the 60s and 70s, many of them centered on matters of race, I associate those times with images of red-faced individuals confronting one another, not infrequently accompanied by fists, even guns. Sometimes soldiers or militias or mobs.