From UChicago News:

Michael Levin: Pretty much everything, birth defects, traumatic injury, aging, degenerative disease, cancer, all of these things boil down to the problem of a group of cells not knowing how or not being able to build the right thing. If we have the answer to this, how do you communicate an anatomical goals to a collection of cells? You could fix all of these things.

Michael Levin: Pretty much everything, birth defects, traumatic injury, aging, degenerative disease, cancer, all of these things boil down to the problem of a group of cells not knowing how or not being able to build the right thing. If we have the answer to this, how do you communicate an anatomical goals to a collection of cells? You could fix all of these things.

Paul Rand: We have this assumption that our cells are mindless, that they’re hardwired to only do a limited set of things, but Levin isn’t so sure.

Michael Levin: We sort of think that, “Okay, so there’s the chemistry, it’s sort of unfolds and well, what else could it possibly do? It’s just following the laws of chemistry?” That robustness, it actually lulls us into a very false sense of simplicity because, for example, if you take a human or many other kinds of embryos and you cut them in half, you don’t get two half bodies the way that you would get if you cut a car or a computer or something else in half, you get two perfectly normal monozygotic twins, and the way that happens is because that collection of cells can tell that half of it is missing and it can tell that it needs to rebuild what’s missing? That process right there is literally a kind of intelligence, and once you’ve understood that the body, much like the brain, is a collective intelligence and the morphogenesis is the behavior of that collective intelligence, you can start to ask all sorts of interesting questions. How can you train it? How do you know what it’s thinking? How do you communicate with it?

Paul Rand: Levin thinks he may have found the answers to those questions, bioelectricity.

More here.

Will you please consider becoming a supporter of 3QD by clicking here now? We wouldn’t ask for your support if we did not need it to keep the site running. And, of course, you will get the added benefit of no longer seeing any distracting ads on the site. Thank you!

Will you please consider becoming a supporter of 3QD by clicking here now? We wouldn’t ask for your support if we did not need it to keep the site running. And, of course, you will get the added benefit of no longer seeing any distracting ads on the site. Thank you!

TAKE A GOOD LOOK

TAKE A GOOD LOOK Michael Levin: Pretty much everything, birth defects, traumatic injury, aging, degenerative disease, cancer, all of these things boil down to the problem of a group of cells not knowing how or not being able to build the right thing. If we have the answer to this, how do you communicate an anatomical goals to a collection of cells? You could fix all of these things.

Michael Levin: Pretty much everything, birth defects, traumatic injury, aging, degenerative disease, cancer, all of these things boil down to the problem of a group of cells not knowing how or not being able to build the right thing. If we have the answer to this, how do you communicate an anatomical goals to a collection of cells? You could fix all of these things. “For generations in the mind of America, the Negro has been more of a formula than a human being—a something to be argued about, condemned or defended, to be ‘kept down,’ or ‘in his place,’ or ‘helped up,’ to be worried with or worried over, harassed or patronized, a social bogey or a social burden.” So wrote Alain Locke in the anthology The New Negro (1925), often considered the founding document of the Harlem Renaissance, the artistic movement of which Locke is generally recognized as intellectual impresario. “The thinking Negro even has been induced to share this same general attitude, to focus his attention on controversial issues, to see himself in the distorted perspective of a social problem. His shadow, so to speak, has been more real to him than his personality.”

“For generations in the mind of America, the Negro has been more of a formula than a human being—a something to be argued about, condemned or defended, to be ‘kept down,’ or ‘in his place,’ or ‘helped up,’ to be worried with or worried over, harassed or patronized, a social bogey or a social burden.” So wrote Alain Locke in the anthology The New Negro (1925), often considered the founding document of the Harlem Renaissance, the artistic movement of which Locke is generally recognized as intellectual impresario. “The thinking Negro even has been induced to share this same general attitude, to focus his attention on controversial issues, to see himself in the distorted perspective of a social problem. His shadow, so to speak, has been more real to him than his personality.” Modern pro wrestling branches off from vaudeville, loops back through the circus, launches off a theater balcony, and takes a detour past Muscle Beach before hammering together a space all its own. It’s held onto its malleability and perennial status as a home for misfits and weirdos who don’t quite fit in anywhere else. As an accessible working-class art form, it’s become a magnet for generations of performers who came into wrestling with little more than a dream and a high pain threshold. It’s not a coincidence that pro wrestling is one of the few theatrical arts in which a performer can still succeed wholly on their own merits. You don’t need rich parents or a degree from a prestigious institution to don the tights and become a star; it’ll still cost you and the view from backstage isn’t always pretty, but the barrier to entry is far lower. How do you get to Wrestlemania? Practice.

Modern pro wrestling branches off from vaudeville, loops back through the circus, launches off a theater balcony, and takes a detour past Muscle Beach before hammering together a space all its own. It’s held onto its malleability and perennial status as a home for misfits and weirdos who don’t quite fit in anywhere else. As an accessible working-class art form, it’s become a magnet for generations of performers who came into wrestling with little more than a dream and a high pain threshold. It’s not a coincidence that pro wrestling is one of the few theatrical arts in which a performer can still succeed wholly on their own merits. You don’t need rich parents or a degree from a prestigious institution to don the tights and become a star; it’ll still cost you and the view from backstage isn’t always pretty, but the barrier to entry is far lower. How do you get to Wrestlemania? Practice. In 2022, researchers at the Bee Sensory and Behavioral Ecology Lab at Queen Mary University of London observed bumblebees doing something remarkable: The diminutive, fuzzy creatures were engaging in activity that

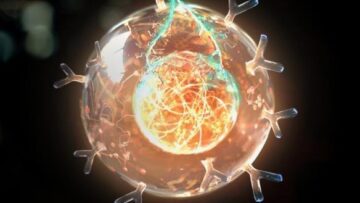

In 2022, researchers at the Bee Sensory and Behavioral Ecology Lab at Queen Mary University of London observed bumblebees doing something remarkable: The diminutive, fuzzy creatures were engaging in activity that  Dubbed “living drugs,” CAR T cells are bioengineered from a patient’s own immune cells to make them better able to hunt and destroy cancer. The treatment is successfully tackling previously untreatable blood cancers. Six therapies are already approved by the FDA.

Dubbed “living drugs,” CAR T cells are bioengineered from a patient’s own immune cells to make them better able to hunt and destroy cancer. The treatment is successfully tackling previously untreatable blood cancers. Six therapies are already approved by the FDA.  Years ago, for reasons I still don’t fully understand, I found myself writing about flight. It started as just a few paragraphs, a bit of spontaneous fiction jotted down in a notebook: a man stood on the roof of a barn, wearing a pair of enormous wings built from wood and cloth. His friend on the ground—the narrator—looked on nervously, ready to call an ambulance. And then the man jumped. Somehow, he flew.

Years ago, for reasons I still don’t fully understand, I found myself writing about flight. It started as just a few paragraphs, a bit of spontaneous fiction jotted down in a notebook: a man stood on the roof of a barn, wearing a pair of enormous wings built from wood and cloth. His friend on the ground—the narrator—looked on nervously, ready to call an ambulance. And then the man jumped. Somehow, he flew. After they were released from prison in Paris in the late autumn of 1794, both having narrowly escaped the guillotine, new bosom friends Rose de Beauharnais and Térézia Tallien found they had nothing to wear. Dressmakers and milliners had all but disappeared from a city still reeling from the Reign of Terror. In an era of desperate need and rampant inflation, a time when even the most prosperous took candles and bread with them when they went out to dinner, who could afford a silk dress, still less stays, hoops, acres of petticoats and several maids to sew you into it?

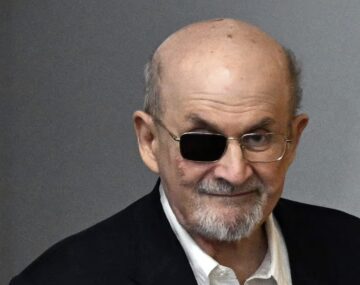

After they were released from prison in Paris in the late autumn of 1794, both having narrowly escaped the guillotine, new bosom friends Rose de Beauharnais and Térézia Tallien found they had nothing to wear. Dressmakers and milliners had all but disappeared from a city still reeling from the Reign of Terror. In an era of desperate need and rampant inflation, a time when even the most prosperous took candles and bread with them when they went out to dinner, who could afford a silk dress, still less stays, hoops, acres of petticoats and several maids to sew you into it? ‘At a quarter to eleven on August 12, 2022, on a sunny Friday morning in upstate New York, I was attacked and almost killed by a young man with a knife,” begins Salman Rushdie’s new memoir.

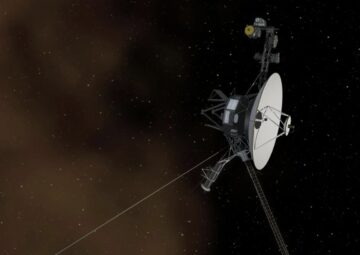

‘At a quarter to eleven on August 12, 2022, on a sunny Friday morning in upstate New York, I was attacked and almost killed by a young man with a knife,” begins Salman Rushdie’s new memoir. NASA’s interstellar explorer Voyager 1 is finally communicating with ground control in an understandable way again. On Saturday (April 20), Voyager 1 updated ground control about its health status for the first time in 5 months. While the

NASA’s interstellar explorer Voyager 1 is finally communicating with ground control in an understandable way again. On Saturday (April 20), Voyager 1 updated ground control about its health status for the first time in 5 months. While the  Kwame Anthony Appiah is a British-Ghanaian philosopher, Professor of Philosophy and Law and New York University, and the “Ethicist” columnist for The New York Times Magazine.

Kwame Anthony Appiah is a British-Ghanaian philosopher, Professor of Philosophy and Law and New York University, and the “Ethicist” columnist for The New York Times Magazine. “Where is Ahmad?” The soldier called my name while we were stopped at the last Israeli checkpoint on the way from Ramallah to Jerusalem. I am a Palestinian American. But once I’m in my ancestral homeland, I’m not an American in the eyes of Israeli authorities. I am simply Palestinian, denied the basic right to movement and pilgrimage to the Holy Land. For too long, Palestinians in the diaspora, like myself, became travelers on our soil. We tried to forget the realities of occupation in the West Bank, and that a few hours south in Gaza our brothers and sisters suffered under even more

“Where is Ahmad?” The soldier called my name while we were stopped at the last Israeli checkpoint on the way from Ramallah to Jerusalem. I am a Palestinian American. But once I’m in my ancestral homeland, I’m not an American in the eyes of Israeli authorities. I am simply Palestinian, denied the basic right to movement and pilgrimage to the Holy Land. For too long, Palestinians in the diaspora, like myself, became travelers on our soil. We tried to forget the realities of occupation in the West Bank, and that a few hours south in Gaza our brothers and sisters suffered under even more  If you put a lab mouse on a diet, cutting the animal’s caloric intake by 30 to 40 percent, it will live, on average, about 30 percent longer. The calorie restriction, as the intervention is technically called, can’t be so extreme that the animal is malnourished, but it should be aggressive enough to trigger some key biological changes. Scientists

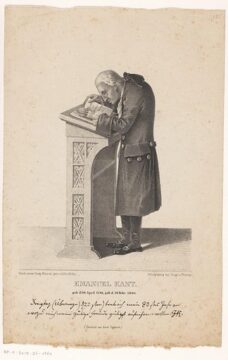

If you put a lab mouse on a diet, cutting the animal’s caloric intake by 30 to 40 percent, it will live, on average, about 30 percent longer. The calorie restriction, as the intervention is technically called, can’t be so extreme that the animal is malnourished, but it should be aggressive enough to trigger some key biological changes. Scientists  Kant’s views here are taken by many philosophers to be an impossible attempt to have it both ways. Kant seems to be arguing that evil is necessarily attributed to each of us, apparently rooted in human nature. And yet at the same time he claims that evil is freely chosen: each of us is fully responsible for this unavoidable human predicament. But how is this possible? How could a condition “entwined with humanity itself” be something that “come[s] about through one’s own fault”?

Kant’s views here are taken by many philosophers to be an impossible attempt to have it both ways. Kant seems to be arguing that evil is necessarily attributed to each of us, apparently rooted in human nature. And yet at the same time he claims that evil is freely chosen: each of us is fully responsible for this unavoidable human predicament. But how is this possible? How could a condition “entwined with humanity itself” be something that “come[s] about through one’s own fault”?