by Thomas Fernandes

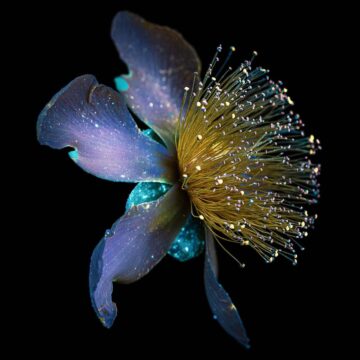

This series began with the desire to share a more diverse and lifelike account of biodiversity than the more mediatized utilitarian framing used in reporting, awareness campaigns, or pleas for conservation. This position is far from unique; the philosopher Arne Naess articulated the deep ecology movement more than 30 years ago, in which the first two principles are:

- The well-being and flourishing of human and nonhuman life on Earth have value in themselves. These inherent values are independent of the usefulness of the nonhuman world for human purposes.

- Richness and diversity of life-forms are also values in themselves.

Valuing life for its own sake is something few would oppose in principle. Yet the reality of this value is tested only when choices must be made, at which points commitment to abstract principles often dissolves first. But these principles don’t have to remain abstract. Writing these essays made me care more about biodiversity than when I started. Not through moral argument, but through familiarity. Learning about vultures did more to make me care about their extinction than any reasonable arguments. Closeness came from spending time in their world, not from being told they matter. It is hard to care for the alien.

Yet valuing life for its sake does not mean it does not have value for us. Yes, ecological value, but also in enabling a change in perspective. We get stuck in perceptual ruts so deep we cannot imagine alternatives. We assume our way of seeing is simply how things are.

This is the core of Donald Hoffman’s Interface Theory of Perception, in which he challenges the idea that perception reconstructs the objective properties of the world as they really are. Instead, he argues that perception actively constructs the perceptual world of an organism. What we experience are not faithful renderings of reality, but species-specific solutions shaped by evolution. Read more »

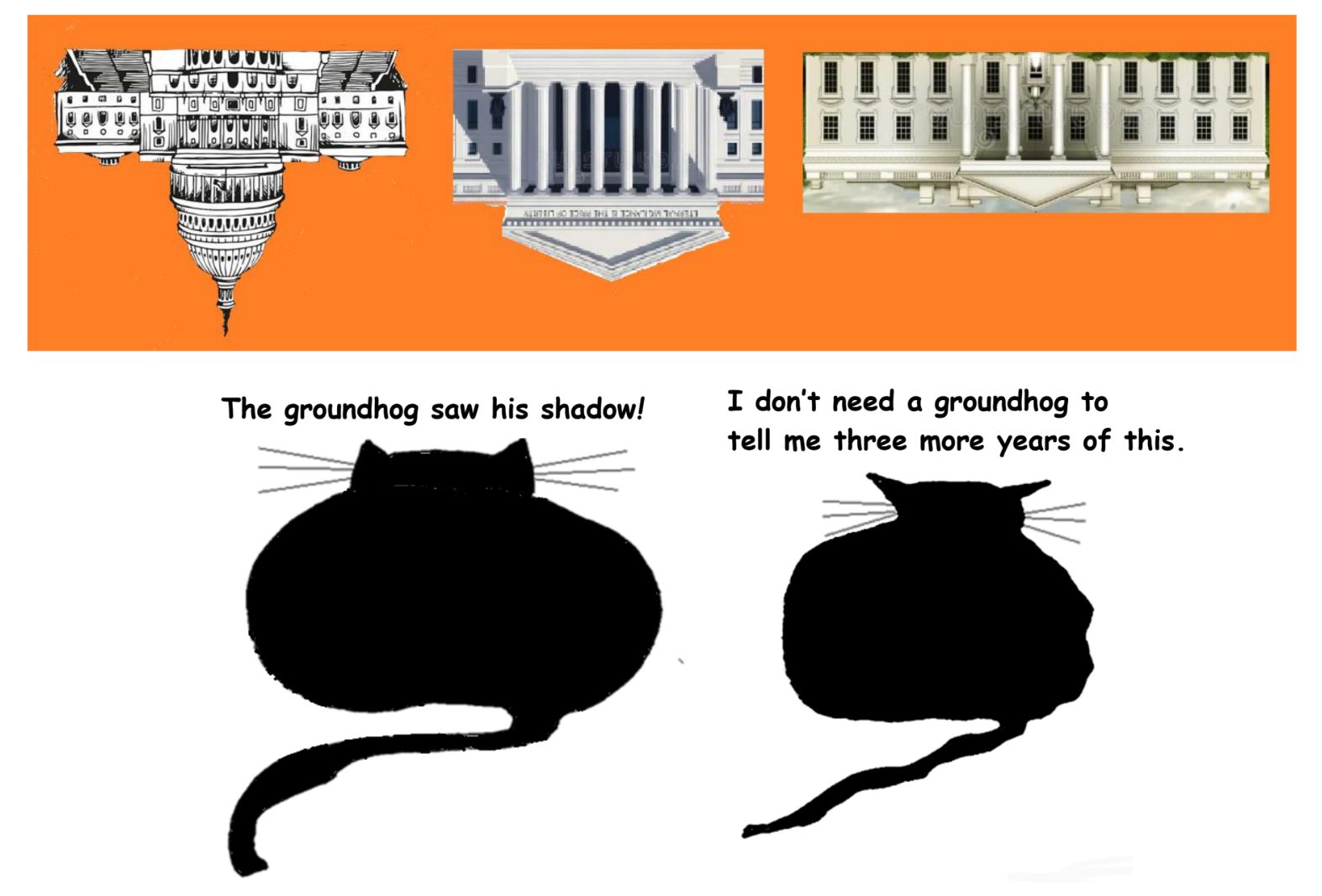

An era of worldwide illiberal governance approaches. If the Trump administration has its way, future illiberal leaders will face fewer opponents. Aspiring autocrats will lose the constraint of the United States as a potential opponent. Autocracy will spread.

An era of worldwide illiberal governance approaches. If the Trump administration has its way, future illiberal leaders will face fewer opponents. Aspiring autocrats will lose the constraint of the United States as a potential opponent. Autocracy will spread. Alia Farid. From the series “Elsewhere”. Produced by Chisenhale Gallery, London. Commissioned by Chisenhale Gallery; Passerelle Centre d’art contemporain, Brest.

Alia Farid. From the series “Elsewhere”. Produced by Chisenhale Gallery, London. Commissioned by Chisenhale Gallery; Passerelle Centre d’art contemporain, Brest.