by Eric J. Weiner

There are two ways to be fooled. One is to believe what isn’t true; the other is to refuse to believe what is true. ― Soren Kierkegaard

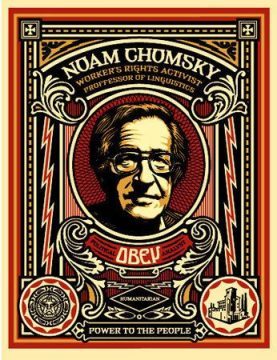

A lot has changed since 1967, the year Noam Chomsky published “The Responsibility of Intellectuals.” His essay threw damning shade at the intelligentsia—particularly those in the social and political sciences—as well as those that supported what he called the “cult of expertise,” an ideological formation of professors, philosophers, scientists, military strategists, economists, technocrats, and foreign policy wonks, some of who believed the general public was ill-equipped (i.e., too stupid) to make decisions about the Vietnam war without experts to make it for them. For others in this cult, the public represented a real threat to established power and its operations in Vietnam, not because they were too stupid to understand foreign policy, but because they would understand it all too well. They had a sense that the public, if they learned the facts, wouldn’t support their foreign policy. Of course, in retrospect, we know that this is exactly what happened. Once the facts of the operation leaked out or were exposed by Chomsky and others like him, the majority of people disagreed with the “experts.” Soon there were new experts to provide rationalizations for why and how the old experts got it wrong, but not before a groundswell of popular protest and resistance turned the political tide and gave a glimpse at the power of everyday people—the “excesses of democracy”—to control the fate of the nation and the world.

A lot has changed since 1967, the year Noam Chomsky published “The Responsibility of Intellectuals.” His essay threw damning shade at the intelligentsia—particularly those in the social and political sciences—as well as those that supported what he called the “cult of expertise,” an ideological formation of professors, philosophers, scientists, military strategists, economists, technocrats, and foreign policy wonks, some of who believed the general public was ill-equipped (i.e., too stupid) to make decisions about the Vietnam war without experts to make it for them. For others in this cult, the public represented a real threat to established power and its operations in Vietnam, not because they were too stupid to understand foreign policy, but because they would understand it all too well. They had a sense that the public, if they learned the facts, wouldn’t support their foreign policy. Of course, in retrospect, we know that this is exactly what happened. Once the facts of the operation leaked out or were exposed by Chomsky and others like him, the majority of people disagreed with the “experts.” Soon there were new experts to provide rationalizations for why and how the old experts got it wrong, but not before a groundswell of popular protest and resistance turned the political tide and gave a glimpse at the power of everyday people—the “excesses of democracy”—to control the fate of the nation and the world.

Chomsky has consistently been confident that people who were not considered experts in foreign affairs were as capable if not more so to decide what was right and wrong without the expert as a guide. This is one of the things that continues to make Chomsky such a threat to the established order. He has faith in the public’s ability to think critically (i.e., reasonably, morally, and logically) about foreign affairs and other governmental actions at the local and national levels. For Chomsky, the promise of democracy begins and ends with the people. He does not have the same confidence that those in positions of power will give the public the facts so that they can make good and reasonable decisions. But this does not mean that Chomsky uncritically embraces the public simply because it is the public. He does not support, nor has he ever, the cult of willful ignorance; that is, those members of the public—experts, intellectuals or laypeople—who, as Kierkegaard wrote, “refuse to believe what is true.”

Chomsky has consistently been confident that people who were not considered experts in foreign affairs were as capable if not more so to decide what was right and wrong without the expert as a guide. This is one of the things that continues to make Chomsky such a threat to the established order. He has faith in the public’s ability to think critically (i.e., reasonably, morally, and logically) about foreign affairs and other governmental actions at the local and national levels. For Chomsky, the promise of democracy begins and ends with the people. He does not have the same confidence that those in positions of power will give the public the facts so that they can make good and reasonable decisions. But this does not mean that Chomsky uncritically embraces the public simply because it is the public. He does not support, nor has he ever, the cult of willful ignorance; that is, those members of the public—experts, intellectuals or laypeople—who, as Kierkegaard wrote, “refuse to believe what is true.”

He is not a relativist and thinks postmodern theory is incoherent. Truth, for Chomsky, is not a relative concept. Rather, he believes in the need for an educated citizenry that can think logically and reasonably about pressing social and political issues. An educated citizenry with free access to factual information can evaluate the information independent of expert analysis. He contends that if democracy is to have any chance of success then people have to be educated in a way that provides them the tools to be able to critically evaluate information for whether it is true and also decide if the actions that the information implies are ethical. Without this kind of educated citizenry, democracy, according to Chomsky (and many others), will surely collapse and eventually be replaced by some form of authoritarianism.

Because he is recognized, by fans and critics alike, as a leading public intellectual as well as an expert in the fields of philosophy and linguistics, some have read Chomsky’s views on the intellectual and the official role of experts as ironic at best and hypocritical at worse. But maybe the criticism arises from the way language is being used to obfuscate rather than elucidate truth. For Chomsky, the essential responsibility of intellectuals “is to speak the truth and to expose lies.” From this perspective, Chomsky’s issue is not with the intellectual but with those who identify as such but do not function in this way. Those who have been identified as intellectuals but do not function in this capacity are pseudo-intellectuals (charlatans) at best and, at worse, are using their authority to undercut civic agency, perpetuate the status-quo, support established power and its abuses, and manufacture consent for ideas and policies that run counter to the interests of those outside of official power. Chomsky is neither against intellectuals nor the value of having expertise but rather critical of people who use the title “intellectual” and “expert” to impose untruths and veil lies behind a distortion of facts, omission of information, jargon and/or unnecessarily complex language, a project of miseducation, censorship, and by blocking access to information that should be available in a free and democratic society.

Intellectuals, in order to be able “to speak the truth and expose lies” must understand how ideology works in the form of official institutions and everyday life. Ideological analysis is not simple and requires specific knowledge and skills. My grandfather, who had an 8th grade education and grew up a very poor, Jewish refugee from Russia, had this knowledge and these skills. He was a voracious reader and essentially self-educated. He functioned as an intellectual although his expertise was in managing a television and electronics repair store. One had little or nothing to do with the other. Yet he was committed to speaking the truth and was capable of exposing lies because of his literacy and self-education. He was not schooled, but rather was educated through his reading of history, social theory, philosophy, political science, biographies, and religion. He had a deep and wide-ranging library. Having served in WWI, he came back a pacifist, horrified by the destruction and suffering he experienced. He was also a “card-carrying” socialist, anti-racist, proud American, and active member of his synagogue. He could discern lies through ideological analyses and by reading beyond official accounts. He could evaluate whether something was right or wrong by combining his experiential knowledge with his book knowledge of ethics and morality. His literacy and library card were his keys to becoming a version of Chomsky’s intellectual. What he didn’t have was time. He worked six days a week and five nights. His name was Samuel Oliver Barrish (He would joke that he was a proper SOB). He was born in 1896 and lived 96 years.

In our current historical juncture, Chomsky’s critique of the intellectual and the cult of expertise is still as relevant today as it was in 1967, yet complicated by a hegemonic surge of anti-intellectualism and the established cult of willful ignorance. In short, anti-intellectualism is a suspicion and outright rejection of complexity, reasoned analysis, facts, and grounded theory. From Ph.D.’s to high school drop-outs and everyone in between, anti-intellectualism is an equal opportunity employer, attracting people from all walks of life who must work hard to remain wrapped in a veil ignorance. Of course, anti-intellectuals would never acknowledge their anti-intellectualism as a form of ignorance. Rather, these people are happily members of the cult of willful ignorance, refusing, as Kierkegaard wrote, “to believe what is true,” especially when what is true challenges or contradicts what they think they know.

More generally, anti-intellectualism is a state of mind; a set of social practices; a network of associations; a formation of knowledge; a Discourse; a tribal identification; a circuit of intertextual mediums that deliver content; a set of dispositions, propositions and attitudes; a structure of power and authority; and a transformative cultural and political force. In the modern university generally, and in certain colleges and departments more specifically (i.e., education, teacher-training, business, finance), anti-intellectualism has been institutionalized at an ideological level. Instrumentality rules with the power of commonsense, while the work of intellectuals is marginalized, dismissed as impractical, or considered beyond the scope of their academic and institutional responsibilities. Outside of the university, anti-intellectualism has found its champion in a president who rejects any facts that challenge his authority, while gleefully and without irony manufacturing “alternative facts” from the mantel of power/knowledge.

Anti-intellectualism of this nature arises like smoke from the fires of neoliberal capitalism, neo-conservatism, reductive masculinist ideology, certain expressions of working-class culture, intransigent forms of identity politics, positivism, and the liberal wings of academia. Within these overlapping contexts, the work of intellectuals signals a form of labor that has no recognizable value within capitalist ideology because it can’t easily be commodified (this doesn’t mean it hasn’t); carries connotations of privilege and elitism; is perceived as left-leaning and an attack on tradition; effeminate because it is disconnected from manual labor; and politically impotent because of its tendency to embrace a form of post-modern relativity.

From silos on the Left and Right, the intellectual is dismissed as out-of-touch, disconnected from the real-world problems of everyday people who are struggling to make ends meet, take the kids to after-school activities, feed their families, fix a leaky toilet, care for their elderly, and walk the dog. In bipartisan fashion, intellectuals are represented as caricatures jabbering incoherently in jargon-riddled language telling the rest of us the right way to act, think, use language, shop, watch media, use technology, and eat. Intellectuals, from this anti-intellectual perspective, are self-righteous and moralistic. Whether or not they act better, they always seem to know better. From silos on the Right, intellectuals are imagined as almost exclusively liberal and more recently as an instrument, however ineffective, of a radical socialist agenda intent on destroying capitalism, gender norms, national identity, and official history. These intellectuals should be feared but also ridiculed for being silly and politically impotent.

Against the backdrop of these representations—the good, bad, and ugly—of the intellectual, I want to briefly discuss the responsibility of intellectuals who teach. For my purposes here, I am not concerned with the age level of the students that are being taught. I will be limiting my comments to the responsibility of intellectuals who teach in formal school settings. Although pedagogy happens through all kinds of medium and within all sorts of institutions, my comments are limited to this population of educators. Intellectuals as teachers, for some reading this, will immediately call to mind Henry Giroux’s influential book Teachers as Intellectuals (1988). Indeed, my thoughts about the responsibility of intellectuals who teach were stirred by his book.

Against the backdrop of these representations—the good, bad, and ugly—of the intellectual, I want to briefly discuss the responsibility of intellectuals who teach. For my purposes here, I am not concerned with the age level of the students that are being taught. I will be limiting my comments to the responsibility of intellectuals who teach in formal school settings. Although pedagogy happens through all kinds of medium and within all sorts of institutions, my comments are limited to this population of educators. Intellectuals as teachers, for some reading this, will immediately call to mind Henry Giroux’s influential book Teachers as Intellectuals (1988). Indeed, my thoughts about the responsibility of intellectuals who teach were stirred by his book.

His book was a critical intervention into what he argued was a hegemonic anti-intellectualism within teacher-education and the teaching profession. What he identified was a form of education that deskilled teachers, preventing them from knowing how to design curriculum and enact pedagogical practices that could challenge the official curriculum. The official curriculum was the curriculum that certain experts had designed and, as many have pointed out over the decades, primarily served the interests of the ruling class, white people, heterosexuals, and men. There is too much literature to review and site regarding the research about the official curriculum, but suffice it to say that I think it is compelling, provocative and uncontroversial.

Teachers as intellectuals, for Giroux and echoing Chomsky, meant that they would speak the truth and uncover lies in the context of their “content-area” knowledge; the official curriculum in their schools, districts, states, and country; and with regard to their pedagogical responsibility to prepare students to be able to participate in democratic life. As one of the thought-developers of “critical pedagogy,” a praxis of teaching and learning that sees schooling as a socializing institution and therefore servicing particular ideological interests, Giroux’s thoughts about teachers as intellectuals add another layer to Chomsky’s in that teachers, in addition to speaking the truth and uncovering lies within the context of schooling, also have an ethical responsibility to teach their students how to recognize and interrogate lies and how to create the conditions by which the truths they are learning to speak can be heard.

Teachers as intellectuals are encouraged to think about their role in the school as a corrective, if needed, to anti-democratic techniques of power. These forces, when naturalized within dominant standards of learning and teaching essentially become invisible to students and teachers alike. But instead of representing a neutral or balanced standard of teaching and curricular design, these forces have historically helped to reproduce the status quo of inequity in terms of race, class, gender, nationalism, and sexuality. As such, teachers as intellectuals who are working within the framework of critical pedagogy have an ethical responsibility to disrupt the continuity of these indoctrinating narratives in an effort to provide students with an opportunity to learn the knowledge, skills, and dispositions to fully participate in democratic institutions. Giroux saw the need for the development of this new kind of teacher—the teacher as intellectual—because of how de-professionalized and de-skilled teachers were and how normalized anti-democratic ideology had become in curriculum and pedagogy. When obeying authority rather than questioning it becomes the sign of a good student (or teacher), we have moved the needle that much farther away from educating a citizenry that can be self-governing. Within the ranks of teacher-education, this move away from democratic skills, knowledge, and dispositions can be seen in the fact that the more educated many of these pre-service and in-service teachers become, the less able they are to speak the truth, uncover lies, and teach their students how to think critically about the workings of ideology, knowledge, and power.

I want to invert Giroux’s framing of the issue, not because teachers are now widely working as intellectuals (his book from 1988 still speaks to a growing problem in teacher-education in 2019), but because there are many intellectuals that teach and have no idea about what it means to be an effective critical educator. So rather than emphasize the intellectual responsibilities of teachers, I want to highlight in broad strokes some of the major pedagogical and curricular responsibilities of intellectuals who teach. I am not going to speak about those “intellectuals” that are not “speaking the truth and uncovering lies.” My thoughts about the responsibilities of intellectuals who teach are confined to those intellectuals who see their essential responsibility as intellectuals as telling the truth and uncovering lies. Bringing this commitment into the classroom and school is easier said than done.

First, there are a few different kinds of responsible intellectuals who teach. This doesn’t, in the end, effect their essential responsibilities, but it may effect how open they are to thinking critically about their role as a teacher. Some intellectuals who teach do it begrudgingly because it is a requirement of their position at a university, college, or other type of school. I call these teacher-intellectuals the” Aristocrats” as they are beholden to no one, rarely if ever wrong, already know everything they need to know, and rule over their classrooms as though it was their fiefdom. The Aristocrats are the hardest to reach because they don’t see themselves as teachers at all and think about teaching as a hinderance and beneath their work as responsible intellectuals. Even though they are committed to speaking the truth and uncovering lies, students are thought of as an inconvenience, theories and practices of teaching and learning are beneath them or beside the point, and curriculum design is no more complicated than compiling a list of books and articles about a topic. Pedagogy is reduced to some form of lecture or “Socratic dialogue,” with the Aristocrat funneling truths and uncovered lies into the empty minds of his/her students. It matters little whether or not the students learn what he/she has taught. If students learn, then that is good. If they do not, then there is probably something wrong with the students.

Another group of intellectual-teachers, I call the “Actors.” This group of intellectual-teachers loves teaching, but primarily because it provides a stage for his/her to disseminate the truths and share the lies he/she has uncovered. The classroom is but a stage and all the students her/his captive audience. An animated and engaging lecturer, the Actor often gets high ratings from her/his students’ teacher evaluations. On “Rate My Professor,” the Actor is consistently praised for being cool, funny, and easy. The Actor needs this kind of affirmation and when the truths s/he shares and the lies s/he uncovers appear to make her/his students uncomfortable, the Actor works hard to soften the effect by creating false equivalences, acknowledging that s/he might be wrong, or changing the subject. The Actor is a relativist in intellectual garb and when threatened with a bad review because s/he has introduced students to uncomfortable truths about the world or themselves, s/he immediately backs off and tries to make the lies and truths relative. S/he does this through an appeal to context, perspective, complexity, and the ambiguity of theory. There is a streak of cowardice that animates the pedagogical work of the Actor. Her/his speech is often punctuated by the rhetorical strategy of creating false equivalences and dichotomies where there are none by framing the issue with the phrase, “On the one hand…but on the other hand…” Even though s/he knows that teaching students to think critically about whatever it is s/he is teaching can result in them “blaming the messenger,” s/he is ultimately more concerned with being “liked” than with being a responsible intellectual-teacher. The more “likes” s/he receives, the more she performs to her audience’s expectations. These may or may not support speaking the truth and uncovering lies.

The next group of intellectual-teachers I call the “Wizards.” This group embraces, without irony or apology, post-modern theories about truths and lies. This does not mean that they ignore the truth or hide lies. It also doesn’t mean that they don’t find value in speaking truths and uncovering lies. Rather, the Wizards spend most of their time on exploring complexity through a theoretical analysis of changing historical contexts, situated perspectives of intersectional identities, post-structural views of language/signs/signifiers, and power/knowledge dynamics that are “always already” conditioning our everyday experiences. The Wizard doesn’t care too much if the students don’t like him/her but s/he is troubled as to why they always seem so confused. Complexity for the Wizards is not a diversion as it is for the cowardly Actor but an honest attempt to struggle with what they understand as the historicity of truth and lies. These intellectual-teachers will speak truths and uncover lies, but immediately put air quotes around almost everything in order to signal to their bewildered students the relativity of whatever truth they have spoken and whatever lie they have uncovered. Theoretically incoherent, pedagogically confusing, and ethically relative, they never seem to be able to come to any concrete conclusions about what to do in the face of the truths and lies that they have been teaching. But they are incredibly enthusiastic, creative and committed to understanding the slippery social, cultural and political conditions that construct our intersectional identities and give people and/or deny them access to real opportunities. Co-optation and commodification are real risks for the Wizards, as there are not any fixed meanings upon which to get their political footing, and frankly, the more slippery the slope, the better.

The last group of intellectual-teachers I will discuss are the “Neo-Critics.” These folks have no issue with courage, likability, speaking the truth, or uncovering lies. Critique is their “tool” of choice and they enter the classroom ready to expose not only the lies but the liars as well. The truth is something that is spoken loudly, without nuance, caveat, or the complication of intersecting contexts of time or place. If the Wizards drift too far into relativism, then the Neo-Critics can put too many eggs into the basket of modernity. Their work is both theoretical, drawing energy from a diversity of thinkers across disciplines, within “high” and “popular” culture, as well as being historical in nature. The Neo-Critics are, in the lexicon of the day, social justice warriors, the implication being that they speak the truth and uncover lies in the service of not just helping students understand oppression but by using their authority as teachers to work with students to overcome it. The line between Neo-Critics as teachers vs. activists can be a fine line that can be easily and problematically crossed.

Using their position as intellectual-teachers, they take explicit positions against racism, sexism, homophobia and other forms of oppression and violence. They do this in the name of honesty and authenticity, arguing that students, if they know what the teacher’s position is, can argue against it. Generally astute to the workings of power, the Neo-Critics blind spot regarding inequity within the context of the classroom can be befuddling. How they take a position might be the difference between becoming the very thing they rail against, namely another force that is silencing, marginalizing, and, in its own way, oppressive to certain groups. To be an effective educator, how one represents the truth and uncovers lies has a lot to do with how deeply the students learn about these truths and lies. This is how and why it is possible for the responsible intellectual to become an ineffective intellectual-teacher. In the worst instance, the responsible intellectual in speaking the truth and uncovering lies does not in the end teach his/her students anything, but instead repels the students away from the truth, with the uncovered lies hiding in plain sight behind her/his students’ ideological biases. In short, the Neo-Critic can be, and often is, theoretically right, but pedagogically wrong.

In broad strokes, here are some things the Aristocrats, Actors, Wizards, and Neo-Critics—all responsible intellectuals—might want to think about as they design their curriculum and perform their pedagogies so that the truths they speak and the lies they uncover can be learned by the students they teach.

1. Begin with where your students are, not where you want them to be. Your students are not empty-headed, docile bodies waiting expectantly for your knowledge. They come to your class with their heads full of ideas, bodies vibrating with experiences, and family histories running through their veins. They are subjects of learning, not objects. As such, they need to be included to varying degrees in the learning process.

2. Teaching is performative. Our voice must be calibrated to the tenor of the time, place, and people we are teaching. We must find a way to be both authentic as well as sensitive to the fact that the way we represent ourselves has an impact on how deeply our students learn from us. I don’t believe we can be effective for all students under all conditions all the time. But we can try to embody and represent intellectual integrity, a commitment to their learning, a respect for their knowledge and experience, and a will to learn how they best learn. Honesty, humility and humor go a long way in creating an environment that is conducive to tackling difficult truths and lies. Conversely, arrogance, apathy, and moral ambiguity play less well.

3. We are not only located in a particular time and place, but we are located in terms of our cultural identities. When we enter the classroom, our students assign us a race/ethnicity, gender, class, sexuality, and religion. They may not be conscious of making these assignments, but they do make them and there are pedagogical implications to knowing and anticipating what these assignments are. What are the dominant meanings of these identifications in the time and place in which you teach? What are the assumptions students may have about you if they are reading and accepting these dominant scripts? Rather than ignore these identifications as though you are not indeed speaking about your topic from a particular location, acknowledge how these identifications are shaping your attitudes and perspectives about the truths of which you speak and the lies you uncover. The inverse is also true in relation to your students’ relationship to truth and lies and your assignment of identities to them.

4. When speaking the truth and uncovering lies in the classroom, students will become uncomfortable for a variety of reasons. This is not only unavoidable, but desirable. However, students have to feel comfortable being uncomfortable. This is not always possible and it is certainly not an easy thing to create. Trust, tolerance, and respect are three important ingredients that a teacher needs to be adding to the classroom environment in order to have any chance of not alienating some students. When the truths you speak and the lies you uncover challenge the deeply learned lessons of a student’s past, the reaction can be quite disturbing. From shutting down to aggressively resisting the veracity of the truths you are speaking about, students who are in this state of heightened anger and fear are less likely to be able to unlearn the lies they have been taught in order to reflect on the truths that you speak. It’s important to understand how disturbing it can be for students to learn truths that upset their fundamental ideas about whatever it is you are teaching them. Belief systems that were thought to be grounded in systems of truth come with a whole set of rules for behavior, thought, identity, etc. When we disrupt these belief systems without recognizing how disturbing these disruptions can be on our student’s sense of identity, then we miss an opportunity to deepen their critical understanding of their relationship to whatever it is you are trying to teach them.

5. Be kind, compassionate, and realize students are in a vulnerable state in relation to the power they have in the school. Although they do have “unofficial” power to disrupt, demean, demonize, resist, refuse, deny, etc., the real disciplinary power of schooling is manifested in our authority to assess their work, determine curriculum, and structure classroom pedagogies and assignments. The deep mistrust that many students have of teachers arises from an abuse of this authority or a perceived abuse of this authority. Either take the grades off the table, or be crystal clear as to what your expectations are. But make sure your expectations for their learning are coherent in the context of your teaching. When a teacher is progressive pedagogically, but conservative/traditional in terms of assessment, there is an incoherence that tells students the teacher is not really as progressive as their pedagogy suggests. What do you want your students to know, why should they know it, and how are you going to measure their learning? Are all of these considerations consistent with your understanding of what it means to be a responsible intellectual-teacher?

I could continue, but I’ve been told by friends that I write too much and need to shorten these essays. So, I’ll conclude by simply saying that becoming a consistently responsible intellectual is increasingly difficult because of the hegemony of the cult of willful ignorance in combination with the audacity of those in positions of official power who collectively lie with a recklessness not seen in modern times. This makes being a consistently responsible intellectual-teacher also more difficult. Speaking the truth and uncovering lies in a way that is pedagogically critical and transformative while being sensitive to student diversity across a variety of disciplines and school-based contexts has always been challenging. Doing it in this toxic environment is not without considerable risk.