From Delanceyplace:

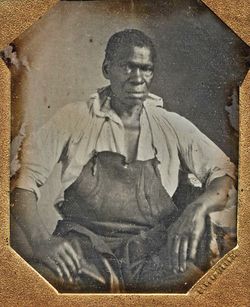

In today's selection — the paradox between Thomas Jefferson's authorship of the Declaration of Independence and his ownership of slaves. When he drafted the Declaration of Independence Jefferson wrote that the slave trade was an “execrable commerce …this assemblage of horrors,” a “cruel war against human nature itself, violating its most sacred rights of life & liberties.” Yet when he had the opportunity in 1817 due to a bequest from Revolutionary War hero Thaddeus Kosciuszko, he did not free his slaves. Jefferson owned more than 600 slaves in his lifetime and at any given time approximately 100 slaves lived on Monticello. In 1792, Jefferson calculated that he was making a 4 percent profit per year on the birth of black children. Jefferson's nail boys alone produced 5,000 to 10,000 nails a day, for a gross income of $2000 in 1796, $35,000 in 2013. “With five simple words in the Declaration of Independence — 'all men are created equal' — Thomas Jefferson undid Aristotle's ancient formula, which had governed human affairs until 1776: 'From the hour of their birth, some men are marked out for subjection, others for rule.' In his original draft of the Declaration, in soaring, damning, fiery prose, Jefferson denounced the slave trade as an 'execrable commerce …this assemblage of horrors,' a 'cruel war against human nature itself, violating its most sacred rights of life & liberties.' …

“But in the 1790s, … 'the most remarkable thing about Jefferson's stand on slavery is his immense silence.' And later, [historian David Brion] Davis finds, Jefferson's emancipation efforts 'virtually ceased.' …”In 1817, Jefferson's old friend, the Revolutionary War hero Thaddeus Kosciuszko, died in Switzerland. The Polish nobleman, who had arrived from Europe in 1776 to aid the Americans, left a substantial fortune to Jefferson. Kosciuszko bequeathed funds to free Jefferson's slaves and purchase land and farming equipment for them to begin a life on their own. In the spring of 1819, Jefferson pondered what to do with the legacy. Kosciuszko had made him executor of the will, so Jefferson had a legal duty, as well as a personal obligation to his deceased friend, to carry out the terms of the document. “The terms came as no surprise to Jefferson. He had helped Kosciuszko draft the will, which states, 'I hereby authorize my friend, Thomas Jefferson, to employ the whole [bequest] in purchasing Negroes from his own or any others and giving them liberty in my name.' Kosciuszko's estate was nearly $20,000, the equivalent today of roughly $280,000. But Jefferson refused the gift, even though it would have reduced the debt hanging over Monticello, while also relieving him, in part at least, of what he himself had described in 1814 as the 'moral reproach' of slavery.

“But in the 1790s, … 'the most remarkable thing about Jefferson's stand on slavery is his immense silence.' And later, [historian David Brion] Davis finds, Jefferson's emancipation efforts 'virtually ceased.' …”In 1817, Jefferson's old friend, the Revolutionary War hero Thaddeus Kosciuszko, died in Switzerland. The Polish nobleman, who had arrived from Europe in 1776 to aid the Americans, left a substantial fortune to Jefferson. Kosciuszko bequeathed funds to free Jefferson's slaves and purchase land and farming equipment for them to begin a life on their own. In the spring of 1819, Jefferson pondered what to do with the legacy. Kosciuszko had made him executor of the will, so Jefferson had a legal duty, as well as a personal obligation to his deceased friend, to carry out the terms of the document. “The terms came as no surprise to Jefferson. He had helped Kosciuszko draft the will, which states, 'I hereby authorize my friend, Thomas Jefferson, to employ the whole [bequest] in purchasing Negroes from his own or any others and giving them liberty in my name.' Kosciuszko's estate was nearly $20,000, the equivalent today of roughly $280,000. But Jefferson refused the gift, even though it would have reduced the debt hanging over Monticello, while also relieving him, in part at least, of what he himself had described in 1814 as the 'moral reproach' of slavery.

More here.

The World Economic Forum ranks Japan a dismal 101st in gender equality out 135 countries — behind Azerbaijan, Indonesia and China. Not a single Nikkei 225 company is run by a woman. Female participation in politics is negligible, and the male-female wage gap is double the average in Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development countries.