Sughra Raza. Finding Color. Boston, January, 2026.

Sughra Raza. Finding Color. Boston, January, 2026.

Digital photograph.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

Sughra Raza. Finding Color. Boston, January, 2026.

Sughra Raza. Finding Color. Boston, January, 2026.

Digital photograph.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

by Herbert Harris

This year’s Black History Month is different.

Black history itself has become contested. Not debated at the margins but questioned at its core. School curricula are scrutinized, and institutions that preserve Black memory are accused of being “divisive.” Should Black history exist, or should it disappear, erasing its many uncomfortable truths and leaving a more homogeneous national narrative?

Narratives are what hold us together as individuals and as societies. To have the wholeness and continuity essential to our survival, our stories must be heard, recognized, and validated by others. Identity is not a monologue in an empty room; it requires an audience and a full cast.

History is our shared narrative. It is how a nation understands what has happened and who it is. It is also how we relate to those who came before us. To deny or erase significant portions of that history is not merely to rearrange a syllabus. It distorts the self-understanding of the entire society. A narrative that excludes central truths becomes brittle. It depends on selective memory and strategic forgetting. That society’s connections to reality inevitably fray, eventually breaking.

As a psychiatrist, I have spent much of my professional life listening to narratives. Read more »

The digital computer emerged out of devices that were built during World War II for cracking codes and calculating artillery tables. Almost as soon as the computer came into existence people were thinking about using it for chess and language. Alan Turing developed Turochamp, an algorithm for playing chess in 1948. Though that algorithm was never implemented, chess became a central topic of AI research, so much so that John McCarthy, who coined the phrase, “artificial intelligence,” would eventually write an article entitled “Chess as the Drosophila of AI.” In 1949 Warren Weaver, then with the Rockefeller Foundation, wrote a memo proposing machine translation. The first public demonstration of machine translation took place in 1954 at the IBM head office in New York and involved 60 Russian sentences.

These two lines of research differed on a philosophical level. AI was a full-on assault on human intelligence. Chess was regarded as the apogee of human intelligence. If we could program a computer to play chess at a championship level, we could program a computer to do anything a human can do. That’s what researchers believed. That’s why chess was so important as a domain of research.

The goal of machine translation was more modest: the reliable translation of documents in one natural language (e.g. Russian) into another natural language (e.g. English). The research programs were correspondingly different and wouldn’t merge/collide until the 1970s with the Speech Understanding Project sponsored by ARPA (the Advanced Research Projects Agency of the Defense Department, now simply DARPA, Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency).

However, I do not intend to recount the history of research in these two areas. As I said, my aim is more philosophical. I’m interested in the radically different nature that these two cases present for AI research. To that end I want to begin by discussing the radically different geometric footprints presented by chess and natural language. With that ground under our feet we can go on to more abstract matters.

When Bach was a busker playing for humble coin

he’d set up his organ in the middle of a square

regardless of pigeons, ignoring the squirrels who sat

poised at its edges waiting for their daily bread. He’d

set to work assembling its pipes from a scaffold of

arpeggios by his baroque means, setting its starts and stops,

its necessary rests and quick resumptions, seeing

in his mind’s-eye each note to come as he’d placed them, just so,

on paper at his desk, simultaneously hearing them

as they would resonate against eardrums in potential

cathedrals of brains— even before a key was touched,

even before a bow was raised,

even before a slender column of breath

was blown into a flute, or drum skins troubled the air,

he’d hear them as he saw them, strung out along

a horizontal lattice of five lines following the lead limits of a cleft,

soaring between and around each other darting out, in and through,

climbing, diving, making unexpected lateral runs between boundaries,

touching, sometimes, the edge of chaos but never veering there,

understanding the limits of all, so that now, having prepped for his

street-corner concerto, this then-unknown would descend from his scaffold

and share with the ordinary world how a tuned mind works in harvesting

song from a universe of stars: collecting their sweet sap, distilling it

into a sonic portrait of a universe that forever lies within the looped

horizon of things.

Jim Culleny, 10/3/22

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

by Christopher Hall

The problem with teleological thinking as far as authoritarianism goes is that we can delude ourselves into believing that, given that we are not in an Orwellian State, and it looks unlikely that we’re going to get there, some of the current kvetching about the current situation may appear to be overblown. Trump, in other words, at some point is going to go away. He is not likely to succeed in cancelling the midterms (although plenty of denial of voters’ rights is probable), and a third term for him seems equally unlikely. When I look at the future, I do envision some kind of American Restoration is a likely scenario, since it seems that there is no one with Trump’s mastery of a bizarre sort of charisma standing on the deck to take his place (J. D. Vance certainly doesn’t have it). A moderate will take over, there will be much reference to norms and standards and, perhaps, if that moderate is a Democrat, some desultory prosecutions. But that restoration will not be, cannot ever be, complete. We know something has permanently changed. The question for us is where that leaves us, and Liberal Capitalist Democracies, now.

As Orwell’s quote – ““The Party told you to reject the evidence of your eyes and ears. It was their final, most essential command.” – floated around the internet (including this site) in the days and weeks after the murders of Renee Good and Alex Pretti, I did worry a bit that, if we were adopting Orwell as our model of political disaster, we may be a bit off the mark. The “command” issued from the Trump administration to “unsee” what we all clearly saw in the videos of the murders was shambolic in a way no directive from the Ministry of Truth could ever be. But that may have been the point; don’t worry that people are going to mock your attempt to control the narrative. Controlling what people see and say isn’t the point – flooding the zone with shit is. Trump’s Ministry of Bullshit is not concerned that many, perhaps most, see through everything he does. He is concerned that enough do not or will not. I’ve written before that there is a difference between control by enforcing silence and control by encouraging noise. What if the hybrid model is the actual goal – to empty out the core of democracy just enough so that the day-to-day experience of it is not substantially changed – and yet, everything is irrevocably different? Our dystopian visions tend to be of the absolute sort, but absolutism is not particularly helpful at the present moment – and we should hope it doesn’t become so.

The Orwellian directive to unsee is a top-down phenomenon, and the penalties for disobedience severe. An alternative of sorts can be found in China Miéville’s 2009 speculative fiction novel, The City & The City. Read more »

by Priya Malhotra

We stand in front of a painting and extol its brilliance. We listen to a piece of music and call it genius. We watch a film and admire its evocativeness. We hold a beautifully designed object and marvel at its simplicity. What we don’t see — what we almost never ask about — are the versions that came before.

The sketch that didn’t work. The canvas painted over. The idea abandoned halfway through. The sculpture that cracked. The notes in the margin that were crossed out.

Art, when we encounter it publicly, looks certain. But art is made in uncertainty.

That’s the simple but powerful idea behind Moving Archives, an exhibition opening this February at Bikaner House in Delhi, curated by Ranjita Chaney and Ruchika Soi. Instead of focusing only on finished works, the show turns toward the material around them — drafts, drawings, scripts, research, documentation. It asks a very basic question: What happens to the process once the product is done?

Because process doesn’t disappear. It just goes out of sight. Think about a painter in a studio. The final canvas might look confident and deliberate. But underneath it are layers — earlier compositions, colors tried and rejected, shapes adjusted and corrected. There are sketchbooks filled with studies that never left the room. There are experiments that didn’t succeed. None of that shows up in the gallery label. Yet without it, the final painting would not exist.

The same is true in other fields. Writers produce draft after draft before a novel feels right. Musicians test melodies and rhythms before a song settles into place. Filmmakers shoot more than they use and shape the story in the edit. Designers build prototypes that wobble, collapse, or feel wrong before landing on the object we admire.

Across disciplines, we are used to seeing the polished result. We are not used to seeing the struggle. Maybe that’s because we like the idea of mastery. We like to imagine that great art arrives fully formed. It’s comforting. It makes genius feel clean.

But creation is rarely clean. It is messy. It involves doubt. It requires throwing things away.

And that is where this exhibition becomes interesting — not just for the art world, but for anyone who has ever tried to make something. Read more »

by Ashutosh Jogalekar

Earlier this week, European investigators concluded that the Russian opposition leader Alexei Navalny had been killed with epibatidine, a toxin unknown in Russia’s natural environment and ordinarily found only in the skin of small, brilliantly colored frogs native to the rainforests of South America. If that conclusion is correct, a molecule shaped in one of the most intricate ecosystems on Earth has completed a journey that ends not in the forest, nor in the laboratory, but in a prison cell. For Putin’s Russia, this is one more marker on the road to political assassination using chemical and biological weapons.

Long before laboratories named it, indigenous communities of the Amazon understood through long experience that certain tiny, extraordinarily bright and beautiful frogs carried extraordinary power in their skin. The knowledge was practical and restrained. It served hunting, survival, and continuity. It was part of a relationship with the living forest in which danger and respect were inseparable. Nothing in that knowledge pointed toward geopolitics or assassination. The molecule existed only within a web of life that had shaped it.

Centuries later, science encountered the same substance and read it differently. At the National Institutes of Health, the chemist John Daly devoted decades to the study of amphibian alkaloids, following faint chemical traces through repeated expeditions, careful collections, and patient analysis. His work was not driven by persistence, by the belief that small natural molecules could reveal deep biological truths. From thousands of specimens and years of attention emerged epibatidine, a molecule isolated from the skin of a poison dart frog endemic to Ecuador and Peru: a structure modest in size yet immense in biological effect, binding human receptors with an affinity evolution had refined without intention. Daly turned into something of a folk hero whose findings resonated beyond the halls of chemistry. Read more »

by David Greer

It’s a magical scene not easily forgotten—snow-covered peaks reflected in calm turquoise lakes ringed by stately pines. It’s a view that likely inspired the romantic ballad “The Blue Canadian Rockies”, about a lonesome guy pining for a faraway sweetheart who unaccountably refuses to abandon the mountains she loves to join him somewhere beyond the sea. Sung by Gene Autry in the 1952 movie of the same name, the tune was later covered by artists as diverse as Jim Reeves, Vera Lynn, The Byrds and, perhaps most plaintively, Wilf Carter a.k.a Montana Slim, who added a longing, contemplative yodel to his rendition.

Now imagine the same picture devoid of snow and with the turquoise waters faded to a murky blur. No magic there, just a dull landscape unworthy of a second glance.

That transition is already underway and starting to accelerate as the impacts of human-caused climate change become more pronounced and global efforts at mitigation become more fractured. As it stands now, the striking turquoise hue of some lakes in the Rockies is already beginning to fade, and the glaciers to which those lakes owe their remarkable color will likely be all but gone in a generation or two, so if you haven’t yet enjoyed the magnificence of the blue Canadian Rockies, now may be the time.

I was recently reminded of this on retrieving the Sunday New York Times from my doorstep a couple of weeks ago. Adding to its usual substantial heft was a separate section titled “52 Places to Go”, an annual feature that reminds readers beset by ice pellets and sleet that winter will eventually end and jets will stand ready to fly you to the destination of your dreams, assuming you haven’t already been deported to the destination of your nightmares.

Only one Canadian location merited mention in the feature—a “limited-time train” excursion through the Canadian Rockies. “The route,” explains the article, “will whisk you to pristine alpine meadows in Alberta, where you can enjoy some of the continent’s most spectacular scenery between Jasper and Banff”. What it neglects to mention is that there is no actual train track connecting Jasper and Banff, only a highway. Read more »

by Jim Hanas

Any sufficiently advanced technology might be indistinguishable from magic, as Arthur C. Clarke said, but even small advances–if well-placed–can seem miraculous. I remember the first time I took an Uber, after years of fumbling in the backs of yellow cabs with balled up bills and misplaced credit cards. The driver stopped at my destination. “What happens now?” I asked. His answer surprised and delighted me. “You get out,” he said.

Any sufficiently advanced technology might be indistinguishable from magic, as Arthur C. Clarke said, but even small advances–if well-placed–can seem miraculous. I remember the first time I took an Uber, after years of fumbling in the backs of yellow cabs with balled up bills and misplaced credit cards. The driver stopped at my destination. “What happens now?” I asked. His answer surprised and delighted me. “You get out,” he said.

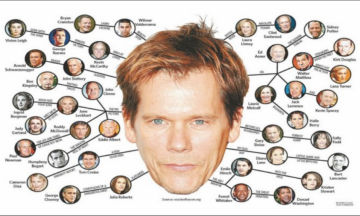

Thirty years ago a website appeared that, in the early days of “the graphical portion of the Internet”–as the New York Times then faithfully called the World Wide Web upon first occurrence–seemed like such a miracle. I am speaking, of course, of the Oracle of Bacon, the site inspired by the parlor game “Six Degrees of Kevin Bacon.” The story of the Oracle, which is maintained to this day, is–in many ways–the history of the consumer Internet in brief. It features a meme, virality, consumer delight, and unintended consequences–but more on those later.

The Oracle is based on a game invented by college students in 1994. An early message board thread titled “Kevin Bacon is the Center of the Universe” challenged readers to find the shortest path between Kevin Bacon and other actors via chains of movies they had appeared in together. The post reported that the game’s initial prompt had “received 80 responses in just over a week” (!) at the University of Virginia, though it was three students at Albright College in Pennsylvania that codified the game–and its benchmark–under the name “Six Degrees of Kevin Bacon,” after the 1993 movie based on the John Guare play of the same name. A book followed in 1996, and–were it not for the contemporaneous explosion of the World Wide Web–the story might have ended there. Read more »

by Ken MacVey

Several years ago I was the moderator of a bar association debate between John Eastman, then dean of Chapman University School of Law, and a dean of another law school. The topic was the Constitution and religion. At one point Eastman argued that the promotion of religious teachings in public school classrooms was backed by the US Constitution. In doing so he appealed to the audience: didn’t they all have the Ten Commandments posted in their classrooms when growing up? Most looked puzzled or shook their heads. No one nodded or said yes. Eastman appeared to have failed to convince anyone of his novel take on the Constitution.

Several years ago I was the moderator of a bar association debate between John Eastman, then dean of Chapman University School of Law, and a dean of another law school. The topic was the Constitution and religion. At one point Eastman argued that the promotion of religious teachings in public school classrooms was backed by the US Constitution. In doing so he appealed to the audience: didn’t they all have the Ten Commandments posted in their classrooms when growing up? Most looked puzzled or shook their heads. No one nodded or said yes. Eastman appeared to have failed to convince anyone of his novel take on the Constitution.

Eastman since has resigned as dean of Chapman Law School and has faced criminal charges and disbarment proceedings regarding his role as a lawyer in the attempted overthrow of the 2020 presidential election that Trump lost. California State Bar judges have recommended Eastman be permanently disbarred, a recommendation that is now pending before the California Supreme Court. But one of Eastman’s constitutional views that once seemed far-fetched may very well be upheld by one court and ultimately the Supreme Court. The Fifth Circuit US Court of Appeals in January heard oral arguments on challenges to statutes in Texas and Louisiana that require displaying the Ten Commandments in every public school classroom in their respective states. By some accounts the oral argument by the challengers was not well received.

Many think it is likely the Fifth Circuit will uphold the constitutionality of the Texas or the Louisiana statute, or both, and that ultimately the matter could be taken up by the Supreme Court. Several Supreme Court justices could be very receptive to their constitutionality despite a 1980 Supreme Court precedent finding mandatory classroom displays of the Ten Commandments unconstitutional. If the Fifth Circuit or the Supreme Court upholds their constitutionality, almost certainly it will be based on an “originalist” interpretation of the Constitution. Read more »

by Lei Wang

My trick for falling asleep is pretending I actually have to get up to do something else.

I imagine that the alarm has just rung, the obligation must be borne—any moment now, I must leave the cocoon to pack for my early flight or send urgent essay feedback—but I am deliciously malingering in bed.

I fall asleep while distracting myself from feeling the need to fall asleep, instead treating sleep as a rebellious act. This psychology is also how I have experienced the best writing in my life on silent meditation retreats where I snuck in contraband notebooks—writing as a forbidden act—and the best meditation and naps at writing residencies where I’m afraid the secret residency police will catch me not writing.

The only other trick I have for falling asleep is fully accepting the awakeness. But they are actually just one trick, the trick of not trying to do the thing I think I am supposed to be doing. This is also the secret to meditation, by the way, and sex. One of my favorite meditations, via Adyashanti, is the No Idea meditation: how would you meditate, how would you write or love or charm someone, if you had no idea what you were supposed to be doing? And thus couldn’t fail?

Once, forgetting my own tricks and trying very hard to be sexy to someone, I was accidentally funny in a way I have always wanted to be, but maybe only to myself. I made witticism after witticism, nervous joke after joke. Puns leapt into my head one after the other, while I completely left my body. I did not seduce the intended.

Emily Dickinson writes:

Tell all the truth but tell it slant—

Success in Circuit lies

Too bright for our infirm Delight

The Truth’s superb surprise

As Lightning to the Children eased

With explanation kind

The Truth must dazzle gradually

Or every man be blind—

These circuitous truths apply to ourselves as well as to others—we must sometimes hide our own truths from ourselves, in order to live them. As every Joan Didion fan knows, this applies to writing. Read more »

I decided to use this week’s photograph to recommend a book rather than post a visually interesting image as I usually try to do. So here’s a low-resolution self-portrait by webcam showing a book which I have found to be an extremely clear-headed discussion of a lot of issues swirling around in the anxiety induced by the presence of the machine intelligences now among us. No doubt I have a somewhat biased view since the author, Blaise Agüera y Arcas, confirms some of my own independent thinking about these issues but I think many people, especially those who are unsure of the relationship between how machine learning works and how our brains work, will find it profitable to go through the detailed explanations provided here. It is not “light” reading by any means but certainly rewards attentive study. You can find more information about the book here and about the author here. And I highly recommend that you read it.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

by Dwight Furrow

The question of whether AI is capable of having conscious experiences is not an abstract philosophical debate. It has real consequences and getting the wrong answer is dangerous. If AI is conscious then we will experience substantial pressure to confer human and individual rights on AI entities, especially if they report experiencing pain or suffering. If AI is not conscious and thus cannot experience pain and suffering, that pressure will be relieved at least up to a point.

The question of whether AI is capable of having conscious experiences is not an abstract philosophical debate. It has real consequences and getting the wrong answer is dangerous. If AI is conscious then we will experience substantial pressure to confer human and individual rights on AI entities, especially if they report experiencing pain or suffering. If AI is not conscious and thus cannot experience pain and suffering, that pressure will be relieved at least up to a point.

It strikes me as extraordinarily dangerous to give super-human intelligence the robust autonomy entailed by human rights. On the other hand, if we deny such rights to AI and it turns out to be conscious, we incur the substantial moral risk of treating a conscious being as a labor-saving device. A fully sentient, super-human intelligence poorly treated will not be happy.

I hear and read a good deal of discussion coming out of Silicon Valley about whether AI is at least potentially conscious. The problem is that—and I mean this quite literally—no one knows what they’re talking about. Because no one knows what consciousness is. This is an enormously complex question with a very long history of debate in philosophy and the sciences. And we are not close to resolving it. There are at least eight main theories of consciousness and countless others striving to get attention. We are unlikely to settle this question quickly so it’s important not to make unwarranted assumptions about such a consequential issue.

This is not the place to articulate all the nuances of that debate and its implications for AI, but I think there is a way of bringing some focus to the question by organizing these various theories as competing views on the status of subjective experience, or to use the more or less technical term, the status of “qualia.” Read more »

by Nils Peterson

I

I’ve been a singer with others most of my life, choruses, choirs, chorales, madrigal groups, barbershop quartets, duets. I love singing, still try to do a little each day, warm up with the computer, doing exercises for voices over 50. In my case, it should be way over 50.

At my senior citizens residence we have a karaoke session about once a month. The guide flashes on the TV screen. You’ve got a mike, the words and accompaniment, and what voice you have left. I specialize in old ballads, the Frank Sinatra and Tony Bennett kinds of songs. My most ambitious vocal was trying to sing like Robert Goulet with “If Ever I Should Leave You” from Camelot. I find karaoke fun. The young people who work at my place do too and join us in performing. The reason I’m writing this is I haven’t known any of the songs, not a one, that the young people have chosen to sing. Not sure if they’ve known any of mine.

But I’ve tried to keep up a bit with popular music. I religiously watch the television show The Voice (a show in which young singers compete against each other) trying to keep up not only with what is being sung, but how it’s being sung. It’s clear there is no place for baritones anymore except in country music. The head voice, what used to be called falsetto, is the dominant male instrument. And yes, that often can make a glorious sound. The words seem to be fairly irrelevant which is a good thing since I usually can’t quite make them out. Yet, I am fond of the show and all of those bright young people showing off by singing.

I too like to show off by singing. Read more »

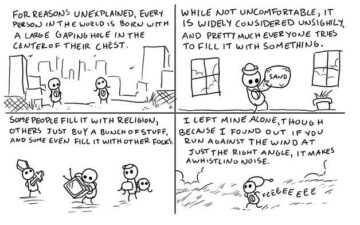

by Tim Sommers

At one point in Sophocles’ Oedipus at Colonus (401 BCE), the chorus offers this bit of wisdom: “Not to be born is, beyond all estimation, best; but when a man has seen the light, the next best is to go whence he came as soon as possible.”

This particular way of putting it is usually traced back to Silenus (700 BCE). However, the view was not an aberration among the Ancient Greeks. Three hundred years later, Aristotle mentions it as a well-known and popular enough view to be the jumping-off point from which to examine alternatives. Plutarch and Herodotus treat it, not as startling pessimistic, but as mainstream.

In the nineteenth century, Schopenhauer said that “Human life must be some kind of mistake.” And implied that “If children were brought into the world by an act of pure reason alone” the human race would not continue to exist.

Contemporary South African philosopher David Benatar agrees. “Coming into existence,” he argues, “is always a serious harm.” And “It would be better to never have been.”

The view that it is morally wrong to bring new people into existence is called antinatalism. General pessimism about life, on the other hand, including ourselves and the lives of people who already exists, tends to be based on empirical claims about the proportion of pleasure to pain in a life. There is no in-principle reason to be sure ahead of time that a life won’t be worth living. Certainly, all the contemporary antinatalists I know of avoid extending the claim that it’s wrong to bring new life into existence to advocating suicide. To be clear, antinatilists do not encourage suicide or think that this view implies anyone should commit suicide.

Suicide may sometimes be justified; for example, to avoid death by torture or a terminal and excruciating illness. And surely there is some connection between the question ‘What if anything gives our lives enough meaning to be worth living?’ and ‘Should we bring new lives into existence?’

In any case, I want to talk about Benatar because he seems to have come up with a new argument to defend antinatalism. A new argument in a debate thousands of years old is worth looking at – even one as depressing as this. Read more »

by Robert Jensen

Wes Jackson’s career demonstrates that sometimes the race goes not to the swift but to the unconventional, that the battle can be won not only by the strong but by the stubborn. Straight-A students don’t always lead the way.

Jackson, one of the last half-century’s most innovative thinkers about regenerative agriculture, has won a MacArthur Fellowship, the so-called “genius grant.” He also received the Right Livelihood Award, often called the “alternative Nobel Prize,” in addition to dozens of other awards from various philanthropic, academic and agricultural organizations. Life Magazine tagged him one of the “100 Important Americans of the 20th Century.”

But mention any of those accolades to Jackson—who was one of the first people to use the term “sustainable agriculture” in print—and he likely will tell the story of almost getting a D in a botany course and describe himself as a misfit.

Not the top of his class

Jackson’s education started in a two-room school near his family’s farm in North Topeka, Kansas, where classes met for only eight months because students were needed for planting and harvest. He was an uneven student whose classroom performance varied depending on the quality of the teacher and his interests at the moment. He went to nearby Kansas Wesleyan University in Salina, focusing as much on football and track as on academics. “I wasn’t what you would call a top student,” Jackson said. “I had a lot of Cs and Bs, an A here and there, but also my share of Ds.” Read more »

Jacob Lawrence. Migration Series (Panel 52).

Jacob Lawrence. Migration Series (Panel 52).

Casein tempera on hardboard.

“…

Spring, 1968. All my students were black, and I wasn’t. Jacob Lawrence, who was teaching a course down the hall from me at Pratt Institute, was a famous artist and a real teacher; I wasn’t either of those things.

When I introduced myself as a third-year undergrad at Pratt and told him about the Life Drawing class I was offering, Mr. Lawrence smiled. I explained that the college was providing a free model and drawing lessons for low-income adults in the area as part of a program I had helped initiate. “Drawing from a live model is important,” he said.

This highly accomplished man, older and far wiser than me, represented a different kind of model. When I asked if he’d say a few words to my class, his smile broadened. Not surprisingly, he made a big hit that evening, and every evening session thereafter, spending almost as much time in my classroom as he did in his. His eye and mind and storytelling skills were always spot-on. Though I remember him as being too kind to say anything too critical about anyone’s work, my students and I learned a great deal.

…

Lawrence’s series of 60 small, unpretentious panels illustrate the journey of the approximately six million African Americans who migrated from the rural South to the urban Northeast, Midwest, and West in the first half of the 20th century. The dream before them: to secure better opportunities for their families and themselves. They would leave segregation and Jim Crow behind. In Lawrence’s paintings, people work, walk, wait, and die. They gather at train stations, school blackboards, and voting machines, as well as in courts, jails, and funerals. At MoMA, I felt the tensions of the arduous exodus he had heard and read about since he was a child. I felt the artist’s great big ambition to tell a great big story in a way that would allow 8- and 80-year-olds alike to understand and experience it. I felt a peoples’ desperation. I felt Black History in my gut.

The Migration Series (1940-41) was originally shown the year it was completed (under the title Migration of the Negro) at the prestigious Downtown Gallery in New York, marking the first time a New York gallery represented an African American artist. Another first: When MoMA bought half the series (all the even-numbered panels; the Phillips Collection in Washington, D.C. bought all the odd numbers), Jacob Lawrence became the first African American to have work included in the Modern’s permanent collection.

From: “Mud Above Sky Below: Love and Death in Jacob Lawrence’s ‘Migration Series'”.

Barry Nemett, July 18, 2015.

Enjoying the content on 3QD? Help keep us going by donating now.

by Sherman J. Clark

We do not need philosophers to tell us that human beings matter. Various versions of that conviction is already at work everywhere we look. A sense that people are worthwhile shapes our law, which punishes cruelty and demands equal treatment. It animates our medicine, which labors to preserve lives that might seem, by some external measure, not worth the cost. It structures our families, where we care for the very young and the very old without calculating returns. It haunts our politics, where arguments about justice presuppose that citizens possess a standing that power must respect. But what does it mean to say human beings are worthwhile? And why might it be worthwhile to ask what me mean when we say we matter?

We do not need philosophers to tell us that human beings matter. Various versions of that conviction is already at work everywhere we look. A sense that people are worthwhile shapes our law, which punishes cruelty and demands equal treatment. It animates our medicine, which labors to preserve lives that might seem, by some external measure, not worth the cost. It structures our families, where we care for the very young and the very old without calculating returns. It haunts our politics, where arguments about justice presuppose that citizens possess a standing that power must respect. But what does it mean to say human beings are worthwhile? And why might it be worthwhile to ask what me mean when we say we matter?

When we speak of dignity, worth, or the respect owed to persons, we are not engaging in idle abstraction. These concepts do real work. They justify constraints on what the powerful may do to the vulnerable. They ground claims to equality that might otherwise seem like mere sentiment. They explain both our moral outrage when persons are degraded and our moral hesitation when we are tempted to treat others as mere instruments.

It is true, then, that we do not need philosophy to tell us that human beings have value. But it is equally true that we are remarkably adept at forgetting this in our actions. We affirm, often sincerely, that all human lives matter, while behaving as though some lives matter far more than others—some kinds of suffering are urgent while others are tolerable, some deaths tragic while others barely register. The conviction is present, but it is unevenly applied, easily displaced by fear, convenience, habit, or interest.

One reason to reflect on the nature and source of human worth, then, is not to discover that worth exists, but to see more clearly how our practices fall short of what we already claim to believe. Thinking about dignity is a way of making our commitments explicit, of exposing the quiet hierarchies we smuggle into our moral lives while insisting, in the abstract, on equality. Philosophy here does not supply a new value; it sharpens our awareness of how badly we sometimes honor the one we already profess.

There is another reason to think carefully about human worth. Read more »

by Claire Chambers

Not long ago I wrote for 3 Quarks Daily about R. K. Narayan’s The Vendor of Sweets. In Narayan’s 1962 novel, a young man comes home to India from studies in the United States of America with an apparently preposterous ambition. Now back in South Asia, he wants to manufacture ‘story-writing machines’ like those that, in this text, already exist in the USA. His father Jagan is horrified; to him, authorship is sacred and human. Furthermore, to this ageing Gandhian, the writing machines sound like just another instance of American ‘Coca-colonization’. Jagan contrasts the machines’ fluent but bloodless writing with what he genders (and ages) as the ‘granny’ oral storyteller of Indian village life.

Not long ago I wrote for 3 Quarks Daily about R. K. Narayan’s The Vendor of Sweets. In Narayan’s 1962 novel, a young man comes home to India from studies in the United States of America with an apparently preposterous ambition. Now back in South Asia, he wants to manufacture ‘story-writing machines’ like those that, in this text, already exist in the USA. His father Jagan is horrified; to him, authorship is sacred and human. Furthermore, to this ageing Gandhian, the writing machines sound like just another instance of American ‘Coca-colonization’. Jagan contrasts the machines’ fluent but bloodless writing with what he genders (and ages) as the ‘granny’ oral storyteller of Indian village life.

Yet here we are in 2026, and this machine isn’t just a twentieth-century satire – it is fast becoming the very air that we breathe in our research and our imaginative endeavours. Being disembodied it may not be able to replace oral storytellers easily, but many other kinds of writers, artists, and creatives are worried about robots taking over their jobs. Generative artificial intelligence entails similar questions about tradition, modernity, global north and global south, colonialism and gender to those Narayan was pondering more than sixty years ago. I will consider all of these questions in this blog post and the sequel(s) which I envision, although I won’t head in a linear trajectory but will instead zigzag. From the outset it needs to be said I am a conflicted doubter in all this, and thus haven’t been able to resolve the conflict. What single individual could?

Anyway, I’ve been following the heated debate on generative AI, and I find myself not only conflicted but in two minds – a for and against I’ll try to sketch in these linked posts. Neither am I sold on the hype, nor am I rejecting the technology out of hand. But I’m fascinated and alarmed by what AI is doing to us. By ‘us’, I mean people who are creative writers, arts and humanities professionals, or simply trying to survive on a combative, burning planet. In other words, what is the impact of the story-writing machines, and how can human beings adapt or resist? Read more »

Anyway, I’ve been following the heated debate on generative AI, and I find myself not only conflicted but in two minds – a for and against I’ll try to sketch in these linked posts. Neither am I sold on the hype, nor am I rejecting the technology out of hand. But I’m fascinated and alarmed by what AI is doing to us. By ‘us’, I mean people who are creative writers, arts and humanities professionals, or simply trying to survive on a combative, burning planet. In other words, what is the impact of the story-writing machines, and how can human beings adapt or resist? Read more »