by Malcolm Murray

Moltbook, the social network for AIs that launched only last week and already has more than a million AI agents, is a clear example of how little we can foresee of the risks that will arise when autonomous AI agents interact. In the first week, the AIs on Moltbook have both already founded their own religion and voiced their need for private communication that humans can’t snoop on. Scott Alexander has a post with many more interesting examples.

This is a clear example of how little we can foresee how AI will be implemented, as well as just plainly independently evolve, as we insert millions, billions or trillions of new intelligences into the societal infrastructure.

The key word describing AI evolution in 2025 was “jaggedness”. While LLM agents had superhuman capabilities in math, coding and science, they still lagged far behind humans in other areas, such as loading the dishwasher or buying something online. LLMs can reach gold-level performance on the International Math Olympiad, but also continue to make simple mistakes showing the forgetfulness and inconsistency of a 5-year old human child. They are on their way to becoming geniuses in a data center, but at this point, they are geniuses of the type that mistake their wife for their hat.

This jagged nature of frontier AI seems as it is a pattern we are stuck with in the current paradigm. Even as models progress, there is no expectation that their performance would suddenly become more uniform. This is perhaps not surprising – there is no general law of intelligence that suggests that intelligence should be uniformly applied. It is not the case with humans or animals, so why would it be the case for machine intelligence? Read more »

Did you ever read Ambrose Bierce’s short story “An Occurrence at Owl Creek Bridge”? If not, it starts as the story of a man who is going to be hanged. As the trap door opens under him, he falls, the rope tightens around his neck but snaps instead of bearing his weight, and he is able to escape from under the gallows. For several pages he wanders through a forest truly sensing the fullness of life in himself and around himself for the first time.

Did you ever read Ambrose Bierce’s short story “An Occurrence at Owl Creek Bridge”? If not, it starts as the story of a man who is going to be hanged. As the trap door opens under him, he falls, the rope tightens around his neck but snaps instead of bearing his weight, and he is able to escape from under the gallows. For several pages he wanders through a forest truly sensing the fullness of life in himself and around himself for the first time.

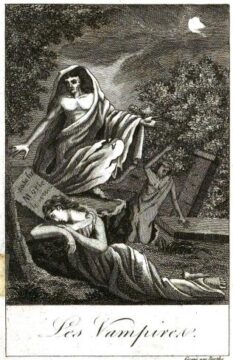

Most fiction tells the story of an outsider—that’s what makes the novel the genre of modernity. But Dracula stands out by giving us a displaced, maladjusted title character with whom it’s impossible to empathize. Think Anna Karenina, Madame Bovary, or Jane Eyre but with Anna, Emma, or Jane spending most of her time offstage, her inner world out of reach, her motivations opaque. Stoker pieces his plot together from diary entries, letters, telegrams, newspaper clippings, even excerpts from a ship’s log. Everyone involved in hunting down the vampire, regardless of how minor or peripheral, has their say. But the voice of the vampire himself is almost absent.

Most fiction tells the story of an outsider—that’s what makes the novel the genre of modernity. But Dracula stands out by giving us a displaced, maladjusted title character with whom it’s impossible to empathize. Think Anna Karenina, Madame Bovary, or Jane Eyre but with Anna, Emma, or Jane spending most of her time offstage, her inner world out of reach, her motivations opaque. Stoker pieces his plot together from diary entries, letters, telegrams, newspaper clippings, even excerpts from a ship’s log. Everyone involved in hunting down the vampire, regardless of how minor or peripheral, has their say. But the voice of the vampire himself is almost absent.

I have put off reading G.H. Hardy’s Mathematician’s Apology (1940) to the end for too long. Now that I have, I can say with conviction that if you ever find yourself needing to justify why people should learn at least some mathematics, then this is the text to avoid, and Hardy provides the arguments you should stay away from furthest. And yet, it grew on me as an honest presentation of Hardy’s perspective on why anything is worth doing.

I have put off reading G.H. Hardy’s Mathematician’s Apology (1940) to the end for too long. Now that I have, I can say with conviction that if you ever find yourself needing to justify why people should learn at least some mathematics, then this is the text to avoid, and Hardy provides the arguments you should stay away from furthest. And yet, it grew on me as an honest presentation of Hardy’s perspective on why anything is worth doing. Sughra Raza. Blood. August 2024.

Sughra Raza. Blood. August 2024.