by Marie Snyder

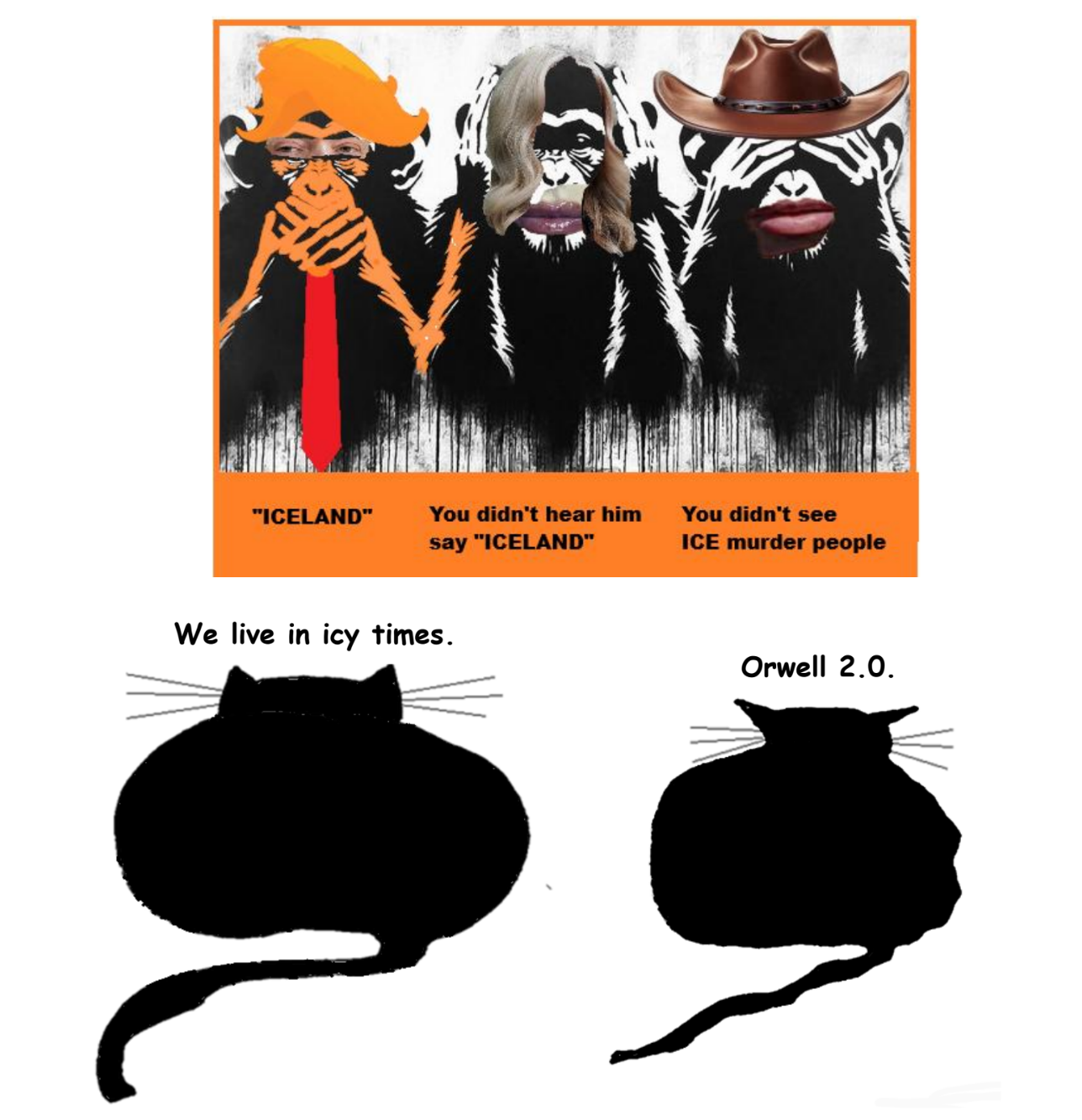

I’ve had several conversations this week about how to be in a time like this when the U.S. government is so overtly corrupted. I’m just the upstairs neighbour in Canada, but we’re high on the list of countries to be overthrown. Even without being in that position, it’s hard to be aware of the world today and not be in a constant state of rage. I mean even more than before. I want to fast forward to the end when all the bad guys go to prison, but that will only happen with ongoing action from as many people as possible. However, that type of action doesn’t necessarily have to be heroic or extraordinary. This is just my two cents from a distance that’s looming closer.

INACTION AS COMPLICITY: What’s Enough?

Viewing newly accepted levels of violence in the U.S. is overwhelming and frightening. A few people have posted lists of things we can do to help, but I wonder if, for many people, it’s asking too much. This might be a controversial view at a time when it feels like we all need to get on board to shift the world back to a less selfish and violent place, but the perspective that we all are complicit if we don’t act might do more harm than good.

Martin Luther King Jr. expressed the sentiment in Stride Toward Freedom: “He who accepts evil without protesting against it is really cooperating with it.” However, the paragraph before gives that statement context: fighting evil includes “withdrawing our coöperation from an evil system” in the bus boycott. They didn’t just stop riding the bus, but people organized carpools, and cab drivers charged the price of bus fare to Black passengers, and others collected money. He also said: “Every man of humane convictions must decide on the protest that best suits his convictions, but we must all protest.” The type of work we do to help has to suit our capacity. Read more »

Did you ever read Ambrose Bierce’s short story “An Occurrence at Owl Creek Bridge”? If not, it starts as the story of a man who is going to be hanged. As the trap door opens under him, he falls, the rope tightens around his neck but snaps instead of bearing his weight, and he is able to escape from under the gallows. For several pages he wanders through a forest truly sensing the fullness of life in himself and around himself for the first time.

Did you ever read Ambrose Bierce’s short story “An Occurrence at Owl Creek Bridge”? If not, it starts as the story of a man who is going to be hanged. As the trap door opens under him, he falls, the rope tightens around his neck but snaps instead of bearing his weight, and he is able to escape from under the gallows. For several pages he wanders through a forest truly sensing the fullness of life in himself and around himself for the first time.

Most fiction tells the story of an outsider—that’s what makes the novel the genre of modernity. But Dracula stands out by giving us a displaced, maladjusted title character with whom it’s impossible to empathize. Think Anna Karenina, Madame Bovary, or Jane Eyre but with Anna, Emma, or Jane spending most of her time offstage, her inner world out of reach, her motivations opaque. Stoker pieces his plot together from diary entries, letters, telegrams, newspaper clippings, even excerpts from a ship’s log. Everyone involved in hunting down the vampire, regardless of how minor or peripheral, has their say. But the voice of the vampire himself is almost absent.

Most fiction tells the story of an outsider—that’s what makes the novel the genre of modernity. But Dracula stands out by giving us a displaced, maladjusted title character with whom it’s impossible to empathize. Think Anna Karenina, Madame Bovary, or Jane Eyre but with Anna, Emma, or Jane spending most of her time offstage, her inner world out of reach, her motivations opaque. Stoker pieces his plot together from diary entries, letters, telegrams, newspaper clippings, even excerpts from a ship’s log. Everyone involved in hunting down the vampire, regardless of how minor or peripheral, has their say. But the voice of the vampire himself is almost absent.

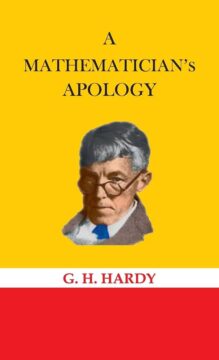

I have put off reading G.H. Hardy’s Mathematician’s Apology (1940) to the end for too long. Now that I have, I can say with conviction that if you ever find yourself needing to justify why people should learn at least some mathematics, then this is the text to avoid, and Hardy provides the arguments you should stay away from furthest. And yet, it grew on me as an honest presentation of Hardy’s perspective on why anything is worth doing.

I have put off reading G.H. Hardy’s Mathematician’s Apology (1940) to the end for too long. Now that I have, I can say with conviction that if you ever find yourself needing to justify why people should learn at least some mathematics, then this is the text to avoid, and Hardy provides the arguments you should stay away from furthest. And yet, it grew on me as an honest presentation of Hardy’s perspective on why anything is worth doing. Sughra Raza. Blood. August 2024.

Sughra Raza. Blood. August 2024.

a prickly pine’s upon one nub,

a prickly pine’s upon one nub,