Rachel Cooke at The Guardian:

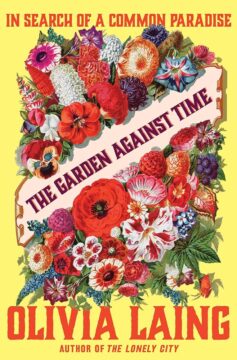

Olivia Laing’s new book, The Garden Against Time, is as fragrantly replete as a long border at its peak. The word that comes to mind is spumy: a blossomy, brimful excess that’s almost too much at times. Here are hundreds of plants, exquisitely described; here is colour, energy and expertise. In a way, it’s akin to a garden itself; a place, almost a park, in which the reader never quite knows what’s around the next corner. But while this is invigorating – my imagination whirred across the verdant expanses of its pages like some crazy, old-fashioned lawnmower – it’s also tiring. Dizzy on its pollen, I often had to put it down. I began to think of the chapter breaks as conveniently placed benches on which I might for a while sit quietly, temporarily unassailed by endless common names, ongoing worries about honey fungus, and long disquisitions on privilege and exclusion.

Olivia Laing’s new book, The Garden Against Time, is as fragrantly replete as a long border at its peak. The word that comes to mind is spumy: a blossomy, brimful excess that’s almost too much at times. Here are hundreds of plants, exquisitely described; here is colour, energy and expertise. In a way, it’s akin to a garden itself; a place, almost a park, in which the reader never quite knows what’s around the next corner. But while this is invigorating – my imagination whirred across the verdant expanses of its pages like some crazy, old-fashioned lawnmower – it’s also tiring. Dizzy on its pollen, I often had to put it down. I began to think of the chapter breaks as conveniently placed benches on which I might for a while sit quietly, temporarily unassailed by endless common names, ongoing worries about honey fungus, and long disquisitions on privilege and exclusion.

Laing does two things at once. First and foremost, this book is a memoir, in which she describes her restoration of the garden attached to the house in Suffolk to which she moved in 2020, as Covid-19 raged on and so many of us sought respite in our backyards, balconies and window boxes (in the course of 2020, more than 3 million people in Britain began to garden for the first time, nearly half of them under 45).

more here.

Will you please consider becoming a supporter of 3QD by clicking here now? We wouldn’t ask for your support if we did not need it to keep the site running. And, of course, you will get the added benefit of no longer seeing any distracting ads on the site. Thank you!

Will you please consider becoming a supporter of 3QD by clicking here now? We wouldn’t ask for your support if we did not need it to keep the site running. And, of course, you will get the added benefit of no longer seeing any distracting ads on the site. Thank you!

O

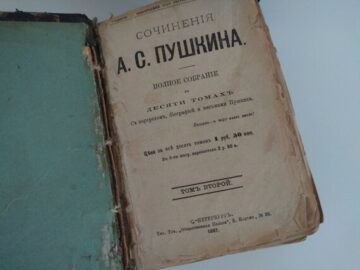

O In April 2022, soon after Russia invaded Ukraine, two men arrived at the library of the University of Tartu, Estonia’s second-largest city. They told the librarians they were Ukrainians fleeing war and asked to consult 19th-century first editions of works by Alexander Pushkin, Russia’s national poet, and Nikolai Gogol. Speaking Russian, they said they were an uncle and nephew researching censorship in czarist Russia so the nephew could apply for a scholarship to the United States. Eager to help, the librarians obliged. The men spent 10 days studying the books.

In April 2022, soon after Russia invaded Ukraine, two men arrived at the library of the University of Tartu, Estonia’s second-largest city. They told the librarians they were Ukrainians fleeing war and asked to consult 19th-century first editions of works by Alexander Pushkin, Russia’s national poet, and Nikolai Gogol. Speaking Russian, they said they were an uncle and nephew researching censorship in czarist Russia so the nephew could apply for a scholarship to the United States. Eager to help, the librarians obliged. The men spent 10 days studying the books. Former President Donald Trump testified in the New York civil fraud trial, earning rebukes from the judge for his off-topic comments. In the editorial cartoon gallery’s lead image, Nick Anderson pokes fun at Trump’s courtroom theatrics by showing him descending a golden escalator to the witness stand, a visual reference to the announcement at Trump Tower of his first presidential bid.

Former President Donald Trump testified in the New York civil fraud trial, earning rebukes from the judge for his off-topic comments. In the editorial cartoon gallery’s lead image, Nick Anderson pokes fun at Trump’s courtroom theatrics by showing him descending a golden escalator to the witness stand, a visual reference to the announcement at Trump Tower of his first presidential bid. Quick pop quiz: Prior to this week, what was Taylor Swift’s last new No. 1 hit on Billboard’s Hot 100?

Quick pop quiz: Prior to this week, what was Taylor Swift’s last new No. 1 hit on Billboard’s Hot 100? In China we have a saying that reading a banned book on a snowy night is one of the true joys of life. From this, one can well imagine the kind of satisfaction that reading a banned book may bring—like candy locked up in a cabinet, it releases a sweet fragrance into solitary spaces. Whenever I travel abroad, I am invariably introduced as China’s most controversial and most censored author. I neither agree nor disagree with this characterization—I’m not bothered by it, but neither do I feel particularly honored by it.

In China we have a saying that reading a banned book on a snowy night is one of the true joys of life. From this, one can well imagine the kind of satisfaction that reading a banned book may bring—like candy locked up in a cabinet, it releases a sweet fragrance into solitary spaces. Whenever I travel abroad, I am invariably introduced as China’s most controversial and most censored author. I neither agree nor disagree with this characterization—I’m not bothered by it, but neither do I feel particularly honored by it. The German forester Peter Wohlleben’s surprise bestseller, The Hidden Life of Trees (published in English in 2016), has inaugurated a new tree discourse, which sees them not as inert objects but

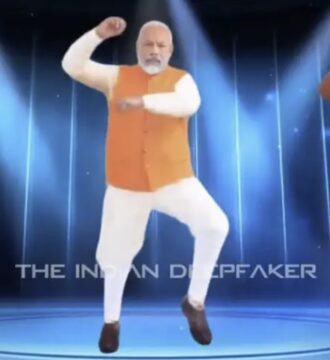

The German forester Peter Wohlleben’s surprise bestseller, The Hidden Life of Trees (published in English in 2016), has inaugurated a new tree discourse, which sees them not as inert objects but  Artificial intelligence is enabling India’s politicians to be everywhere at once in the world’s largest election by cloning their voices and digital likenesses. Even dead public figures, such as politician and actress Jayaram Jayalalithaa, are getting digitally resurrected to canvass support in what is shaping up to be the biggest test yet of democratic elections in the age of

Artificial intelligence is enabling India’s politicians to be everywhere at once in the world’s largest election by cloning their voices and digital likenesses. Even dead public figures, such as politician and actress Jayaram Jayalalithaa, are getting digitally resurrected to canvass support in what is shaping up to be the biggest test yet of democratic elections in the age of  O

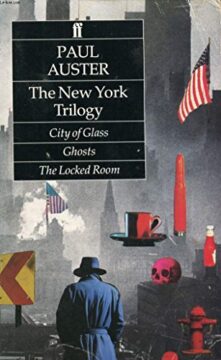

O “It was a wrong number that started it, the telephone ringing three times in the dead of night, and the voice on the other end asking for someone he was not.” So begins City of Glass, the first book in what became Paul Auster’s acclaimed New York Trilogy. Published in 1985, it marked the arrival of a truly unique voice in fiction, one quite distinct from many of the currents in American writing at the time. This was not the minimalism of Raymond Carver, or the expansiveness of Tom Wolfe; this was work much more connected to the traditions of European literature in which Auster was steeped. Paul Auster, who has died at the age of 77 in Brooklyn – where he lived his wife, the writer Siri Hustvedt – leaves a lasting and distinctive legacy in English-language literature.

“It was a wrong number that started it, the telephone ringing three times in the dead of night, and the voice on the other end asking for someone he was not.” So begins City of Glass, the first book in what became Paul Auster’s acclaimed New York Trilogy. Published in 1985, it marked the arrival of a truly unique voice in fiction, one quite distinct from many of the currents in American writing at the time. This was not the minimalism of Raymond Carver, or the expansiveness of Tom Wolfe; this was work much more connected to the traditions of European literature in which Auster was steeped. Paul Auster, who has died at the age of 77 in Brooklyn – where he lived his wife, the writer Siri Hustvedt – leaves a lasting and distinctive legacy in English-language literature. When I was in college, I came across “The Sea and Poison,” a 1950s novel by Shusaku Endo. It tells the story of a doctor in postwar Japan who, as an intern years earlier, participated in a vivisection experiment on an American prisoner. Endo’s lens on the story is not the easiest one, ethically speaking; he doesn’t dwell on the suffering of the victim. Instead, he chooses to explore a more unsettling element: the humanity of the perpetrators.

When I was in college, I came across “The Sea and Poison,” a 1950s novel by Shusaku Endo. It tells the story of a doctor in postwar Japan who, as an intern years earlier, participated in a vivisection experiment on an American prisoner. Endo’s lens on the story is not the easiest one, ethically speaking; he doesn’t dwell on the suffering of the victim. Instead, he chooses to explore a more unsettling element: the humanity of the perpetrators. One of the courses I teach is called “Science, Activism, and Political Conflict,” and one of my ambitions with that course is to show students that both of these things—activism and political conflict—are normal in science, and in academic life more generally. That’s a theme that we like to emphasize when speaking in “defense” of student protest. It’s part of a storied tradition, it’s respectable, it’s normal. But in order to explain why I think what you all are doing is so important, I want to start today by saying that actually, student protest is nowhere near normal enough in the history of higher education in this country. The real scandal is not that there has been student protest. It is that there has not been much, much more of it.

One of the courses I teach is called “Science, Activism, and Political Conflict,” and one of my ambitions with that course is to show students that both of these things—activism and political conflict—are normal in science, and in academic life more generally. That’s a theme that we like to emphasize when speaking in “defense” of student protest. It’s part of a storied tradition, it’s respectable, it’s normal. But in order to explain why I think what you all are doing is so important, I want to start today by saying that actually, student protest is nowhere near normal enough in the history of higher education in this country. The real scandal is not that there has been student protest. It is that there has not been much, much more of it. An artificial intelligence system has proven it can save lives by warning physicians to check on patients whose heart test results indicate a high risk of dying. In a randomised clinical trial with almost 16,000 patients at two hospitals, the AI reduced overall deaths among high-risk patients by 31 per cent.

An artificial intelligence system has proven it can save lives by warning physicians to check on patients whose heart test results indicate a high risk of dying. In a randomised clinical trial with almost 16,000 patients at two hospitals, the AI reduced overall deaths among high-risk patients by 31 per cent. A Moloch Trap is, in simple terms, a zero-sum game. It explains a situation where participants compete for object or outcome X but make something else worse in the process. Everyone competes for X, but in doing so, everyone ends up worse off.

A Moloch Trap is, in simple terms, a zero-sum game. It explains a situation where participants compete for object or outcome X but make something else worse in the process. Everyone competes for X, but in doing so, everyone ends up worse off.